Earlier this semester, Art History Professor Lilien Robinson, BA ’62, MA ’65, showed her undergraduate class on 19th Century European Art a famous 1814 oil painting by the French artist Théodore Géricault titled “An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging.” In it, a mounted Napoleonic cavalry soldier appears to be in mid-attack even as his horse seemingly rears away from the battle. Even though she has studied Géricault for years—and was in the process of writing a journal article that included this very painting—Robinson remained conflicted about whether the French soldier was charging toward an enemy or away from one. So she turned to her students for guidance.

“Is the soldier fighting or retreating?” she asked her class. “What do you think?”

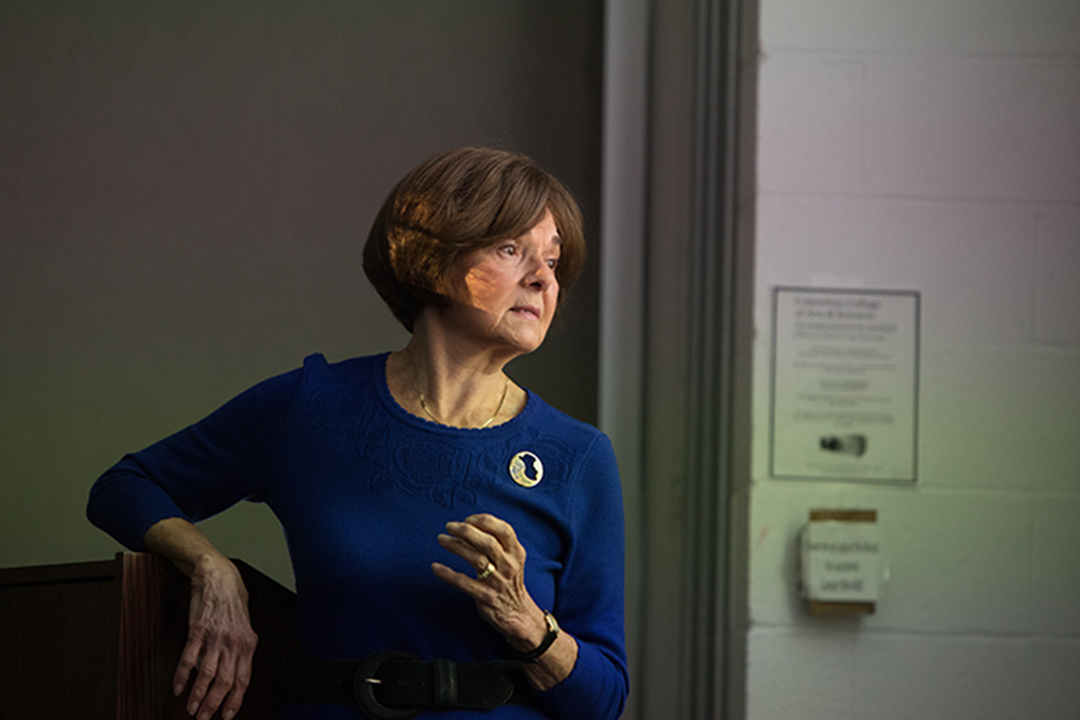

To many of her students, the moment was remarkable. Robinson is a revered professor with five decades of teaching experience and a mantle full of honors such as the Columbian College Excellence in Teaching Award, the Trachtenberg Service Prize and the George Washington University Award. And now she was asking them, her undergraduate students—many of whom had never even taken an art history class before—to help formulate her thoughts.

“As an undergraduate, I never had a professor ask me to respond to their own academic work,” said Elizabeth Brevard Doorly, a second-year art history graduate student who is currently Robinson’s graduate assistant. “But Professor Robinson is a consummate professor. She truly cares for her students and the development of their critical thinking skills.”

For Robinson, each lecture is like a blank canvas. She approaches every class as a fresh opportunity to spark passion in her audience—whether she’s introducing first years to French Realist painters and English Pre-Raphaelites or engaging her graduate seminar in discussions of major collectors from Catherine the Great to Duncan Phillips. As an art history student at Columbian College, Robinson fell under the spell of professors who “conveyed the wonder and excitement that human creativity elicits,” she said. As a GW teacher since 1965, she’s built a reputation as a beloved educator who stays in close contact with her students, some of whom she came to know in her first year teaching. Current and former students routinely send her museum selfies whenever they encounter a new exhibit.

“Lilien inspired in me a lifelong interest in art history and a sustained passion for inquiry,” said Steve Frenkil, BA ’74, a past president of the GW Alumni Association who remains a close friend. “She helped me learn about ways to consider art—techniques that were prevalent at the time; the role of politics and social issues; the implications of artistic, economic and practical constraints on artists; the realities of being an artist in different eras. Saying this makes me want to take her course all over again!”

Grooming Artists and Writers

Growing up in Serbia and living in Switzerland, Robinson developed her love of art early, traveling to view the great collections of the Louvre with a family devoted to creativity. When she arrived at GW, she enrolled in art history classes and was inspired by her instructors, especially former Professor Laurence Leite, a devoted teacher who informed his scholarship with a deep love of art. “Literally I sat on the edge of my chair from the first class on,” she recalled. “After that, there was no question that I was going to teach art history.”

As a professor, Robinson focuses on instilling a heightened appreciation of art both as a historical and an emotional medium. Rather than asking students to memorize dates and style, a typical Robinson class may feature a lively debate over whether students would hang German Romantic Caspar David Friedrich’s “The Monk by the Sea”—a stark portrait of a lone figure—on their bedroom wall. “Some find it inspirational—a contemplation of humanity,” she noted. “Others think it’s a downer. I want a work of art to speak to students. A great painting will offer something new, something different every time we contemplate it.”

Among Robinson’s most difficult, but most rewarding, teaching tasks, is helping students become better writers. When art history major Andrea Gallelli Huezo, BA ’11, MA ’17, first writing assignment was returned covered in edits, my first thought was, ‘I will fail this class.’” But as Huezo turned the pages, she realized Robinson’s edits were more constructive than critical. “She did something no other professor ever did for me—she dedicated hours of her time to push me to become a better writer.”

During her long career, Robinson has heard from those who question the relevance of an art history degree—a claim she dismisses as “foolish.” “I tell them this will make your life better. It will open up so many doors, enriching you both emotionally and intellectually,” she said. “Art history is the most interdisciplinary field I can think of. We approach our study of art in the context of the time: historical events, politics, societal changes and cultural developments.”

As for Gericault’s charging soldier, Robinson’s class determined he was apprehensively turning toward the battle—perhaps in an allusion to the fall of Napoleon. The horse, they concluded, was clearly terrified. Robinson took their insights and included it in a journal article she had been writing about the painting, citing her class for their input. “That respect for her students,” said graduate assistant Doorly, “is an indication of the caliber of her teaching and her caring.”