At a Baltimore City police precinct, Detective Edward Gillespie, BA ’92, leads a classroom of officers through a lesson on procedural justice. But the text he uses isn’t a police manual or a law book. It’s a passage from John Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath. In it, Tom Joad, a Depression-era ex-convict struggling to support his family, describes a beating he endured at the hands of police. The exercise isn’t intended to shame the officers in Gillespie's class, he explains. It’s meant to open their eyes.

“Every day on the street, cops encounter the Joad family,” said Gillespie, a history major. “We meet people who are disenfranchised, people who are afraid, people who are vulnerable and marginalized. The humanities are a window into understanding those people and the conditions within their lives.”

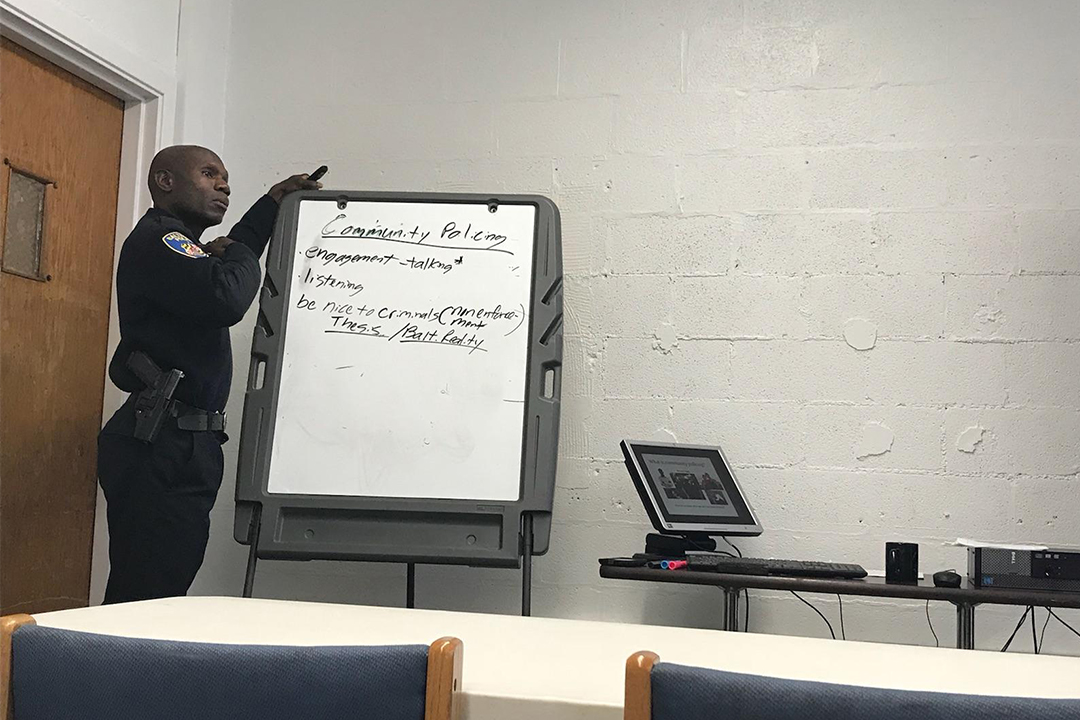

Like other cities around the country, officers in Baltimore—fresh-from-the-academy recruits and veterans alike—spend one to two weeks off the streets and in a classroom for refresher courses and lessons on new police techniques. As a police instructor, Gillespie has taught programs on counter terrorism, de-escalating crises and spotting implicit biases. But his classes are unique. Along with standard law enforcement training, Gillespie believes cops should be introduced to a heavy dose of the humanities. His syllabus eschews defensive tactics and weapons training for Plato, Dostoevsky and James Baldwin. His class is as likely to discuss Camus as crime scenes.

“The humanities are important for what they tell us about the human experience,” Gillespie explained. “Police officers work in a profession in which human experience is not just pertinent but relevant all the time.”

As an undergraduate history student at Columbian College, Gillespie participated in ROTC and intended to join the Marines after graduation. A back injury curtailed his plans, but he put his degree to use as a school teacher in Maryland and Ohio. To advance in his field, he enrolled in a master’s program at Johns Hopkins University, only to have his first classes cancelled on 9/11. After the attack, Gillespie resolved to join the police department once he completed his studies. He earned his liberal arts degree in 2004 and was a member of Baltimore’s first police academy class of 2005.

Gillespie worked beats from auto larceny to gang task forces. When the pressures of police work threatened to overwhelm him, he often fell back on the humanities lessons he learned at GW. “Being out in the city as a cop can be such a culture shock that I would step back from some traumatic incident and think about, for example, something Richard Wright said. Literature, history and philosophy helped me, as a cop, through some difficult situations.”

When he took up his current position as an instructor, he hoped to relay some of those lessons to his fellow officers. His teaching style took on even more significance as questions of police conduct drew local and national scrutiny. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment could offer insight into how desperation can turn ordinary people into criminals. James Baldwin’s essay “A Report from Occupied Territory,” which depicts racially biased policing in 1960s Harlem, led to discussions on the perils of racial profiling. And Plato slipped into Gillespie’s ethics classes to explain how the intellect can override our worst impulses.

His lessons can occasionally draw eye-rolling from jaded veterans. “They think I’m a little eccentric,” he laughed. “When I jump into Plato I say, ‘Just hang with me guys. We are going to ancient Greece for awhile but then I’ll get you right back to Baltimore.’” Gillespie contends the public too often underestimates officers’ desire to broaden their education and improve their policing skills—myths his class hopes to dispel. “Cops are multi-faceted professionals, proud public servants and students of human nature,” he said. “They want to do their jobs the best they can.”