It’s arguably the most important room in the house—the one where meals and memories are made. From person to person and generation to generation, it can alternately feel like a claustrophobic cubby or the heart of the home.

It’s the kitchen. And while many of us feel like we spend our whole lives there, Associate Professor of Writing Caroline J. Smith believes we can still learn a lot about how our kitchens reflect our society—and ourselves.

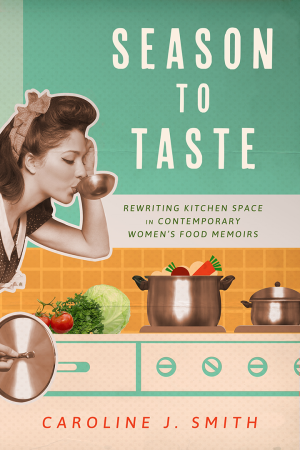

In her new book Season to Taste: Rewriting Kitchen Space in Contemporary Women’s Food Memoirs (University Press of Mississippi, 2023), Smith takes readers on a tour of the ever-shifting kitchen space. Examining food writing through memoirs, recipes and even Better Homes and Gardens articles, she traces the evolution of kitchens since the 1960s—not just from linoleum floors to stainless steel countertops but from feminist movements to contemporary writers. Along the way, she documents how the kitchen has been reframed from a gender prison to a stage for self-discovery.

“In the ’60s, the kitchen was seen as a place for women to escape from,” said Smith, whose previous work has dissected pop culture staples including “chick lit” and the TV series Mad Men. “I was asking how, in the 21st century, women redefined their relationship with this space.”

In an interview with CCAS Spotlight, Smith spoke about changing gender roles, societal shifts and what her own kitchen says about herself.

Q: Your book looks at how changing views of kitchens mirrored women’s changing roles from the ’60s to today. What did feminist writers traditionally think of the kitchen?

A: In second-wave feminist writing, the word that often comes up is “imprisonment.” The kitchen is holding you in, locking you away. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, for example, looked at the “happy housewife heroine” syndrome—these bright, educated, middle-class women who were confined to the home. Friedan was trying to mobilize women to get out of the kitchen and enter into a more active public sphere.

Q: When does the shift back to the kitchen begin?

A: There were isolated individuals even in the ’60s like Julia Child. But it’s really in the first decade of the 21st century that we see a rise in food culture and food writing, particularly by women. As women in society obtained access to public spaces, we started to see this move back to the kitchen. In the book, I look at the different ways women are now using the kitchen to self-actualize and work through their own identities as they reclaim this space. The blogger Shauna James Ahern talks about it as “winking while we bake”—this sense that women are recoding the space of the kitchen to fit contemporary times.

Q: You’ve talk about how our views of the kitchen have evolved. Has the actual physical space changed too?

A: I looked at decades of Better Homes and Gardens to see how they were presenting the kitchen. And we really do see the change in the kitchen space reflecting the change in women’s roles. The ’60s posited the kitchen as this place that’s often contained—shutting women off to the side in a tiny space that’s cut off from the rest of the home. In more contemporary culture, as women moved into the public sphere or workplace, we’ve opened up the kitchen and made it part of the larger home. The walls between the kitchen and the home living space literally disappeared.

Q: What are other big shifts have you seen?

A: The kitchen space was almost exclusively one for women—and mostly white women. But today, men are often portrayed cooking. And there’s less of a whiteness in the space. The most prevalent images of women of color in the kitchen had often been as enslaved or domestic workers. Now we have a more inclusive representation. On her blog, cookbook author Jocelyn Delk Adams flips Friedan’s “happy housewife heroine” on its head by performing the role of the stereotypical housewife as a Black woman. We’re also looking at the kitchen in a less hierarchical way. You don’t have to be a chef to be confident in the kitchen. There doesn’t have to be a separation between professional and private home cooking.

Q: Was this a fun book to write? Did you visit friends’ kitchens? Or try out new recipe?

A: This was a project where I easily got derailed. Reading all these food memoirs and recipes—I’d start cooking instead of writing! I think I was an interior designer in another life. I have always been an avid consumer of architectural magazines and home magazines. I watch home design shows obsessively. So, yes, I looked at Julia Child’s kitchen at the Smithsonian. But I also love to look at other people’s kitchens and ask for house tours. I’m one of those people who loves to drive around the city at night and look in at houses—but not in a creepy way!

Q: So tell us about your own kitchen. What does it say about you?

A: It probably says that I like old things! Both my husband and I are hoarders. We have so much furniture we’ve inherited from grandparents and great aunts and uncles. I think the term they use these days is “cluttercore.” That’s our esthetic right now! But we also had shifts in our own home. We had a very small, closed-off kitchen with no counter space. We remodeled in the last 10 years and now our kitchen is a little retro. It has the black and white floor tile but we’ve opened it up more. We did a lot of research—and watched a lot of HGTV!