By John DiConsiglio

For the faculty and students of the Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology (CASHP), coordinating research activities within the program—much less across other disciplines—once felt as slow-moving as evolution itself. From the hard tissue biology center at Corcoran Hall to the evolutionary neuroscience lab in Ross Hall, the trouble wasn’t a case of uniting scientific specialties or even synchronizing crowded schedules.

The biggest stumbling block was geography.

Until recently, the varied pieces of human paleobiology—from researchers and their experiments to skeletal remains and digital datasets—were scattered across half a dozen buildings. Some labs were hidden in low-ceiling townhouse basements, others in the converted hayloft of an old horse-and-carriage fire station.

“It was virtually impossible for someone from, for example, hard tissue science to drop in on someone from archaeology because they were on the other side of campus,” said Bernard Wood, professor of human origins and CASHP director. And casually consulting with colleagues from the biology or physics departments was out of the question—unless you had the time and patience to navigate city blocks, broken elevators and a labyrinth of twisting staircases and narrow hallways. “I don’t think I’ve ever exchanged more than three sentences with the biologists,” Wood joked.

But the landscape changed for human paleobiology and other GW sciences with last January’s opening of Science and Engineering Hall (SEH), the eight-story, 500,000-square-foot research hub that is now home to 140 faculty members from 10 departments, including four Columbian College disciplines. The state-of-the-art building represents a giant leap forward in core lab facilities, resource capacity and teaching space. Freed from makeshift laboratories in dusty storage rooms, or cross-campus—if not cross-state—commutes, the SEH has cleared the path for the university’s science infrastructure to catch up with its research profile.

“You can’t underestimate the improvement in the size and quality of the new space,” said Assistant Professor of Biology Mollie Manier, who moved her microscopy equipment from a “remodified one-person closet” in Bell Hall to a work space that comfortable fits four people and three microscopes. “It adds a professionalism and a competence to our science culture. This is a place where students say, ‘Wow, we are doing serious research here.’”

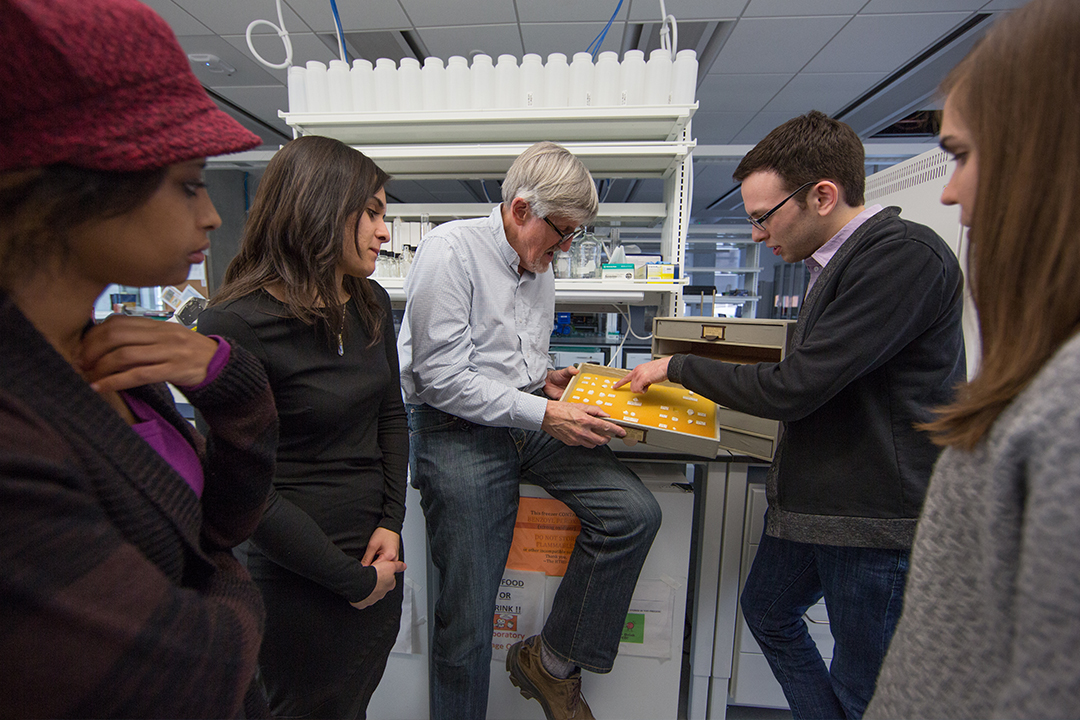

Along with the advancements in facilities and technology, the SEH offers another vital boon to scientific progress: proximity. The building brings together a mix of specialists from physicists and biologists to computer scientists and engineers under one roof. Its open layout, accessibility and lack of physical barriers are intended to break down silos between departments, and to promote cross-disciplinary conversation and inquiry—ultimately leading to collaborations that yield new technologies and discoveries.

“The fact of the matter is that today you cannot do science without collaboration,” said Chemistry Department Chair Michael M. King. “Whether you have an idea that you need somebody else to test or you have an instrument that can solve somebody else’s problem, successful science is all about collaboration. There can’t be any walls between scientists.”

The mix of scientific disciplines at the SEH will “ignite our thoughts and increase our creativity, said Professor of Chemistry Cynthia Dowd.

Now, researchers who might previously have only connected through symposiums and email chains are exchanging ideas in the SEH atriums, common rooms and kitchens, as well as over networking coffees and happy hours. While waiting for a fourth-floor elevator, Assistant Professor of Chemistry Cynthia Dowd and Physics Professor Chen Zeng recently compared notes on trends in tuberculosis and malaria research. When anthropology post-doctoral student Fenna Krienen needed assistance with RNA extraction, she merely walked across the sixth floor to Manier’s biology lab. In the past, when junior biology major Simon Wentworth needed to consult with his computer science counterparts, he schedule a bus ride to the Loudon County-based Virginia Science and Technology Campus. Now, when he’s stumped by a computer algorithm for mapping the genetics of the fat-head minnow, he peeks his head over a glass partition—and asks for help from the computer science majors in the neighboring cubicle.

“Sooner rather than later, those ‘hellos’ will be converted into tangible research,” Wood said. “It’s the natural next step. Once you form these relationships, you begin collaborating. For now, we are enjoying the enthusiasm of anticipation.”

Science and Psyche

Nearly the entire chemistry and human paleobiology faculty now reside in the SEH along with about half the biology department and a third of physics. More science faculty and equipment will be relocated to the new building in the future. But already, King suggested, the SEH has had a hand in recruiting faculty and students. He pointed to Manier as well as Assistant Professor of Biology Scott Powell and Associate Professor of Biology Amy Zanne as faculty members who at least partly based their decision to come to GW on the allure of the new facility.

“SEH was definitely a selling factor,” Manier agreed. And with help from the enhanced prestige of the new facility, the incoming chemistry graduate class will be the biggest in the department’s history, King said. “Top students and faculty want to be in a space where they are surrounded not only by the most modern equipment but also by other people who are making science happen.”

Indeed, for students, the modern teaching laboratories provide hands-on learning opportunities while the larger work spaces have made it easier to interact with both faculty and colleagues from other disciplines. Senior chemistry major Hannah Yi moved from the cramped Corcoran Hall office of Assistant Professor of Chemistry Adelina Voutchkova-Kostal to her state-of-the-art SEH green lab. Yi has already toured Assistant Professor of Biology Hartmut G. Doebel’s bee lab with his research assistants. “We moved from a closed box to a place that is spacious and full of light, where everyone wants to show you what they are working on,” Yi said. “It’s good for your psyche as well as your science.

Before relocating to the SEH, physics’ Zeng and Associate Professor of Chemistry Michael Massiah teamed up on an investigation of a protein in boys that causes birth defects like cleft palates. Their new surroundings have boosted their ongoing collaborative efforts. Massiah’s Corcoran Hall lab was so constrained that student research assistants worked in shifts. But the new chemistry lab has added space for vital resources like autoclaves and walk-in cold rooms. With Massiah and Zeng’s offices mere steps from the shared labs, chemistry and physics students can work in concert while enjoying easy access to their professors.

“Now we can all work together as a team,” Massiah said. “There’s no way to stress how critical that group dynamic is to student learning and to productive scientific collaborations.”

While it may be too early to credit the SEH with sparking new collaborative projects, Dowd said just the potential for an exchange of ideas in labs, classrooms and hallways has everyone from incoming students to veteran researchers brimming with excitement. “We are professional thinkers and it’s hard to think in a bubble,” she said. “The great thing about being together in the SEH is the mix of new blood and expertise. It can only ignite our thoughts and increase our creativity.”