How do you analyze chemical contaminants that are billions of times smaller than a speck of dust? Scientists have long been thwarted in attempts to even detect—much less combat—minute particles that can poison our bodies and our environment. The all-but-invisible chemical threats, conceptualized as 10 times below a billionth of a billionth of a teaspoon of water, have evaded capture from even the most sophisticated technology.

Until now. Professor of Chemistry Akos Vertes recently added a new invention to his long list of accomplishments: a nano-device capable of rapidly identifying materials made up of as little as 100,000 molecules.

“We’re talking about a really, really, really minute amount of material,” Vertes said. “Sample sizes as small as a single yeast cell are sufficient for detailed analysis.”

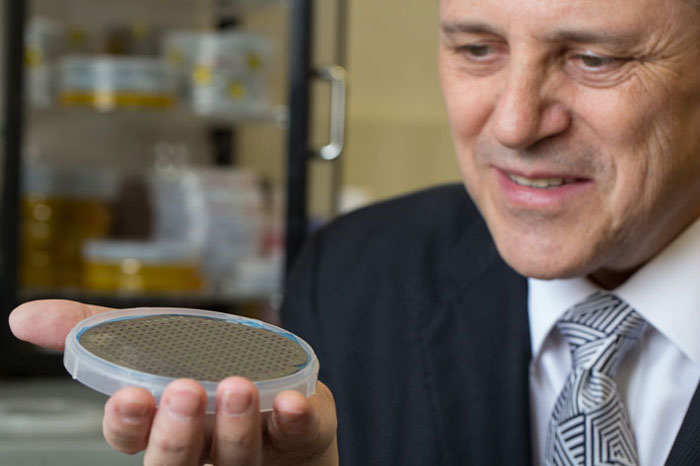

The palm-sized REDIchip (Resonance-Enhanced Desorption Ionization) was designed to uncover these previously undetectable particles and help researchers rapidly identify potential chemical and biological threats. But the technology has wide-ranging applications in multiple fields. The REDIchip can detect drugs in urinalyses, provide earlier detection of emerging health problems, enhance medical imaging, improve tumor margin determinations and identify endocrine disruptors in the environment.

“The extraordinary capability of the REDIchip will easily impact the security, health and environmental sectors, critical drivers of today’s economy,” said Michael King, chair of the Department of Chemistry. “This invention is translational science at its best. It has been exciting to watch the ideas flow from the early stages of the doctoral students in Dr. Vertes’ research group to a patented invention to a commercialized product.”

Commercialized by Protea, the technology was invented with funding from the U.S. Department of Energy and $14.6 million from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The implications for the devise are remarkably widespread. The chip can detect tiny amounts of material in urine, saliva or blood, which could lead to early detection of conditions like diabetes or heart disease. It can analyze hazardous chemicals in the environment, perform chemical imaging and even locate cancer tumors.

The REDIchip can analyze minute amounts of biological and chemical materials that were previously undetectable.

The REDIchip is made of silicon and has rows of disks that reflect light bright neon colors, each consisting of around two million miniscule dots that are 150 nanometers wide—about 500 times smaller than the width of a human hair. After placing the sample on the chip, the researchers put the device into a mass spectrometer. The instrument has a laser that heats up the chips’ small disks and converts them into ions. Finally, the mass spectrometer measures and identifies the ions.

“Let’s say you have a tissue section and there are some cancerous lesions, and you want to identify the metabolic composition inside and outside of the lesion,” Vertes said. “When a surgeon is cutting cancer tissue, the big question is always, how much to cut? I believe our technology can give more accurate, detailed information about tumor margins.”

Currently, Vertes believes the REDIchip will be sold primarily to researchers, pharmaceutical companies and government agencies. Though the technology is hand-held, the needed mass spectrometry equipment is expensive and requires a specialist to be readily available in a doctor’s office.

“That change may come when there is such a compelling advantage from a medical point of view,” Vertes said, “that doctors would say, ‘No matter how expensive, we have to have this.’”