A new study spearheaded by Summer Sheremata, a postdoctoral research fellow in Columbian College’s Attention and Cognition Laboratory, may help decipher how the brain recovers from damaging strokes and could lead to possible therapies to help stroke patients regain at least partial visual perception.

In her paper, “Hemisphere-Dependent Attentional Modulation of Human Parietal Visual Field Representations,” published in The Journal of Neuroscience, Sheremata suggests that the right hemisphere of the brain may be able to assist a damaged left hemisphere in protecting visual attention after a stroke.

|

Summer Sheremata |

“Patients with damage to the right hemisphere often fail to visually perceive objects on their left, but the reverse is much less common. That is, damage to the left hemisphere does not typically lead to deficits in attention,” Sheremata said. “Psychologists have hypothesized that the right hemisphere could help out the left hemisphere in attending to objects on the right, both in healthy individuals and patients recovering from stroke. But until now it remained an assumption.”

Visual attention functions like a spotlight to focus the brain's resources on a specific location or object, Sheremata explained. The world around us is full of far more visual information than our brains can process at any moment. Our visual attention abilities enable our brains to select relevant information and filter out irrelevant information.

For example, while we may see crowds of people as we walk down a street, we generally focus on one factor—the direction in which we are headed or the stoplight at the corner—and pay little attention to the faces of passersby. A stroke may damage our visual attention, making it more difficult for our brains to pick out important information from a myriad of visual details.

Sheremata’s research was conducted at the University of California, Berkeley, with co-author Michael Silver, associate professor of optometry and vision science and neuroscience. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging technology to measure participants’ brain activity, the researchers asked patients to focus their attention in two different ways.

First, the patients were instructed to pay attention to a central box while ignoring a moving object in the background. Then they were asked to do the opposite: ignore the central box and pay attention to the moving background object.

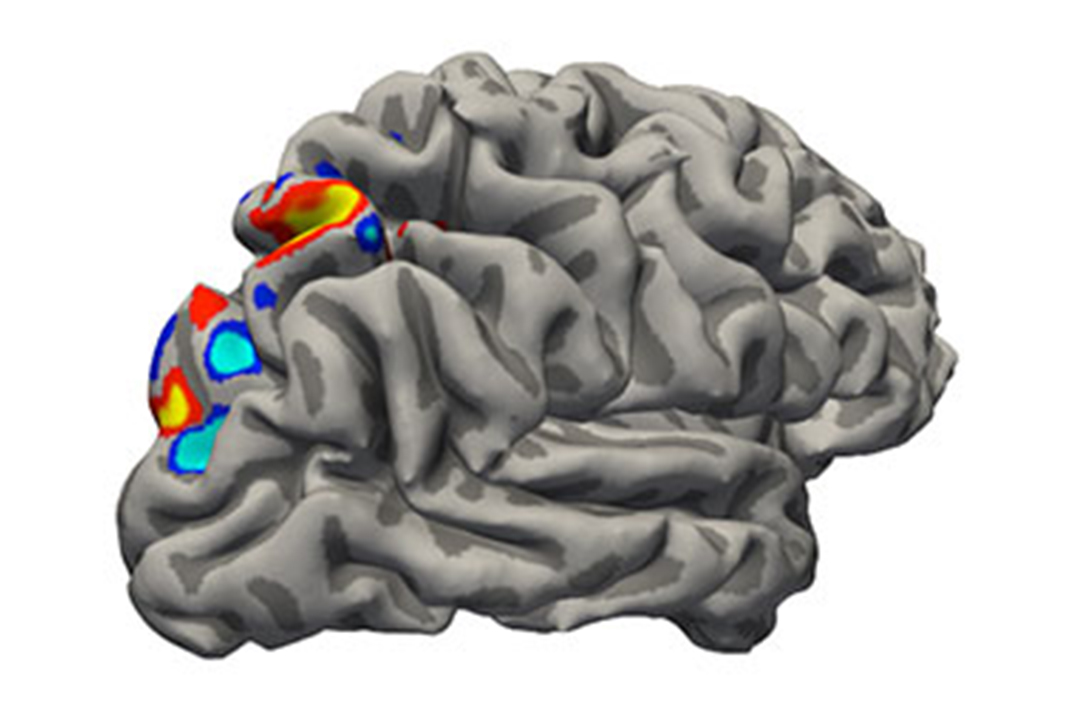

The first scenario measured the patients’ visual response, confirming that the right side of the brain represents the left visual field and that the left side of the brain represents the right visual field. The second scenario tested the effects of visual attention and indicated that, while the left side of the brain only focused on the right visual field, the right side of the brain was able to represent both sides of the visual field.

While the research was conducted on healthy, non-stroke patients, the results suggest a possible brain mechanism for how the visual field can be recovered if it is damaged by a stroke.

“The tasks we do every day change how the brain pays attention to the world around us. By understanding how these changes occur in healthy individuals, we can focus on behaviors that are impaired in stroke patients and provide a focus for rehabilitation,” Sheremata said.

Sheremata’s next round of studies, which will be conducted at GW, will relate her findings to attention and memory functions among stroke patients and healthy individuals.