Pity the Medieval Period. The era stretching from roughly 1000 to 1500 is often dismissed as a wasteland of intellectual and artistic darkness. Overshadowed by Enlightenment stars from Da Vinci to Gutenberg, the Middle Ages calls to mind Game of Thrones-like jousts, Monty Python-mockery and mud-bound feudal serfs. But the period had its highlights. It saw the invention of vertical windmills, eye spectacles and mechanical clocks, as well as the founding of universities like Cambridge and Oxford.

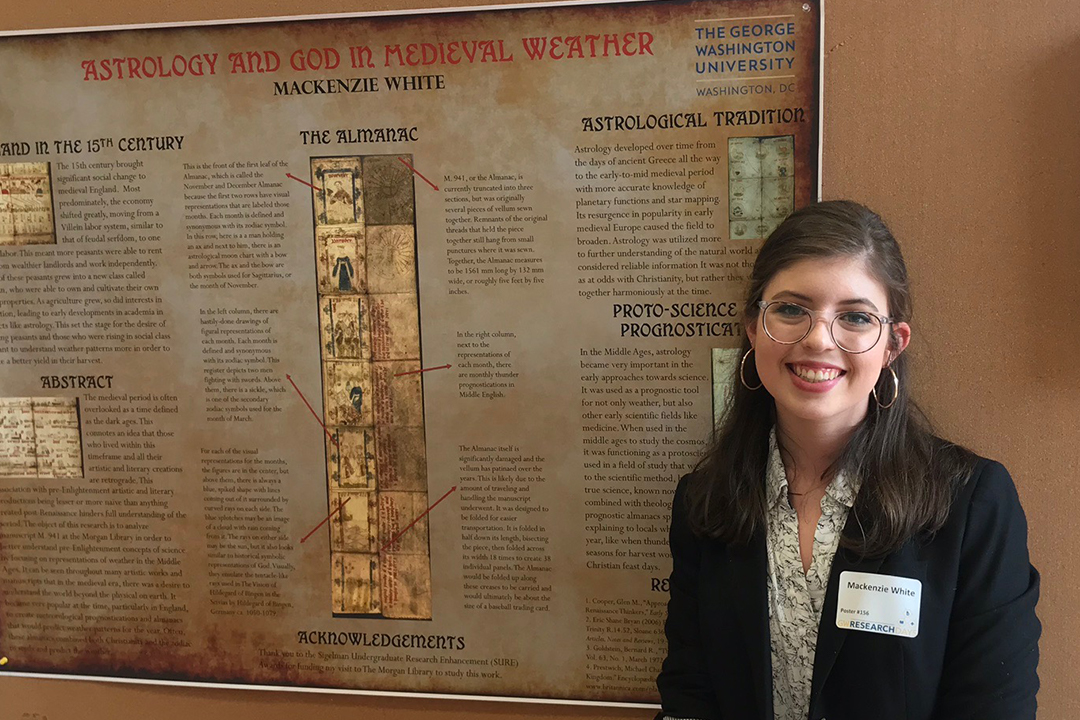

Now art history and political science major Mackenzie White is adding one more overlooked accomplishment to the Medieval short list: Weather forecasting. Over the past year, she has studied the ways Medieval meteorologists combined science, religion and astrology to predict the weather. During the course of her research, she visited historic archives and scoured internet databases to uncover ancient almanacs and study pre-Enlightenment prognosticators. Funded by a Sigelman Undergraduate Research Enhancement (SURE) Award, her work attempts to reclaim the Middle Ages from history’s scorn.

“We think of the Medieval person as uneducated, struggling through the mud and living in a time when everything was terrible,” White said. “Then someone flips a switch and we suddenly get the aesthetics and advances of the Enlightenment. But things were changing in the Middle Ages. And it wasn’t all for the worse.”

For her undergraduate thesis project, White focused on the late Medieval Period—from 1400 to 1500—in a European landscape ravaged by the Crusades and bubonic plague. But social change was on the horizon in Medieval England. The economy was shifting from serfdom to free labor. More peasants rented acres from wealthy landlords as a new class of yeomen owned and cultivated their own small properties. Even educational expansions began to mirror agriculture growth. “The self-awareness that came with economic independence led to a desire among ordinary people to understand the world around them,” White said.

Looking beyond their day-to-day existence, Medieval people often turned to astrology—at the time considered an irrefutable science—for answers to questions about the earth. And for Medieval farmers, similar to those tilling the earth today, their concerns often revolved around the weather.

“If you were a farming peasant or rising in social class, you wanted to understand weather patterns to create a better yield in your harvest,” White explained. “You wanted to know when it would rain and thunder and even when to travel for feast days and saint’s celebrations.”

Suddenly, a new occupation took shape: Medieval weatherman. Astrologers used a combination of observations, Christian myths and the zodiac to create elaborately illustrated almanacs that purported to predict the weather. White examined scores of these calf skin-bound booklets and found that, while Medieval forecasters weren’t especially good at reading weather beyond observable patterns, the almanacs provided a window into the science, culture and thought processes of a little appreciated era.

Most of White’s project focused on a 1433 almanac she discovered in New York City’s Morgan Library. The five-foot-long by five-inch-wide manuscript was designed to fold into a stack of 38 panels—roughly the size of a pack of baseball cards. At the library, she found the almanac significantly weathered, its vellum cracked and patinaed from frequent rough handling by traveling farmers. Remnants of the original threads that held the pieces together still hung from its seams. White didn’t have to don gloves to touch its pages—the risk of tearing a sheet outweighed the threat of skin oil—but she was instructed not to wear nail polish. For the hours that she delicately examined the artifact, a curator stood close by, at one point rushing over to adjust a corner that had shifted off the table’s edge. “You get nervous handling centuries-old documents,” White said.

Almanac owners were often illiterate. In the booklets’ pages, symbols substituted for words. White deciphered many of the meticulously rendered drawings by connecting the dots between zodiac signs and the months of the year. For example, Sagittarius—November—was typically represented by an ax, or, in the 1433 document, the image of a wood-chopping farmer. Another scene depicted two men fighting with swords. Above them was a sickle, one of the zodiac symbols for March. “It’s like figuring out an art puzzle,” she said. “You tease out the meanings from the images.”

White first conceived of her project during a class on religious myth and metaphor taught by Barbara von Barghahn, professor of art history and head of the Art History Program. Von Barghahn introduced her to the idea of Theophanous visions—the notion that God appears to man as physical manifestations in nature, like floods or fire. White’s search for Theophanic art led her to the Medieval almanacs.

Throughout the research process, White sometimes worried that the study of ancient almanacs would only appeal to a niche audience. “I had to ask myself if what I was looking at was something real, something that really had meaning, or was it just fake mumbo jumbo,” she recalled. But she credits her thesis adviser Elizabeth Williams, a former GW Dumbarton Oaks Postdoctoral Fellow and an assistant curator of the Byzantine Collection at Dumbarton Oaks, with encouraging her studies. “Mackenzie’s work disrupts any narratives that medieval people were superstitious or blind followers of tradition or religion,” she said. “She's able to show that scientific thinking wasn't an invention of the Renaissance or Enlightenment.”

“Not a lot of great things happened to people in the Medieval era,” said White, who plans to pursue a master’s degree in museum studies next year. “But they were becoming aware of a world beyond the patch of land they lived on. And if they couldn’t control that world, give them credit for trying to figure it out.”