In 2012, a recovery mission from the U.S. military’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) travelled to Vietnam to investigate the site of a fatal American helicopter crash from 1967. Struck by anti-aircraft artillery, the helicopter hurtled into a central highlands mountainside. Five soldiers were killed, their remains seemingly lost in an explosion of flames and debris.

The 13-person team of soldiers and scientists, including Associate Professor of Anthropology Sarah Wagner, were on a mission to recover any traces of the Missing-In-Action (MIA) military personnel and identify them with the help of sophisticated DNA testing. With the aid of local Vietnamese laborers and the cooperation of the government of Vietnam, they hacked through jungle canopy enveloping the impact crater, emerging after 28 days with a handful of excavated teeth and tiny fragments of bones. Within a year, a tooth was positively identified as belonging to a Marine from Wisconsin. After nearly five decades, his remains were finally returned to his hometown.

For Wagner, a social anthropologist, each MIA service member’s return represents both a personal remembrance and a national narrative on how we commemorate fallen heroes. Her ongoing research examines the efforts to recover, identify and memorialize Vietnam War MIAs—and what they tell us about our institutions and ourselves. Wagner is now chronically her work in a book tentatively entitled Bringing Them Home: Identifying and Remembering Vietnam War MIAs—a project that earned her a coveted 2017-18 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship and a National Endowment of Humanities Public Scholar award.

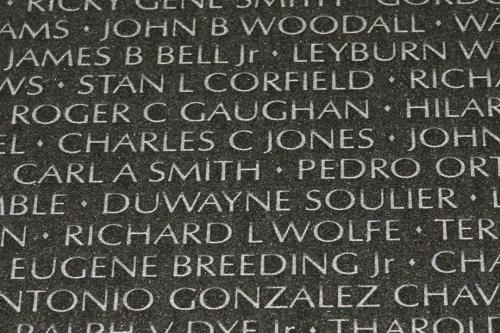

In following the final journeys of missing service members, Wagner has been struck by how today’s recovery and identification efforts—aided by precise DNA testing—have raised the potential of attaching a name to every fallen soldier. These new methodologies, representing the intersection of science and history, are altering our modes of national commemoration, Wagner says, from the collective anonymity of memorials like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to the personalization of individual sacrifices.

“With these homecomings, family members, classmates and neighbors can remember a person not only as a fallen hero but also as a human being,” she said. “He can be more than a symbol. He can be a whole individual welcomed back into the embrace of his country and his community.”

Accounting for the Unaccounted

Wagner’s examination of war loss began in another conflict-torn region: Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2003, as a doctoral student, she spent 16 months in the Balkan nation, initially following refugees from the Srebrenica genocide as they returned to their pre-war homes. She quickly learned that displaced Bosnians were less concerned with their own fate than with locating the remains of murdered loved ones. As mass graves were excavated, she saw families contribute blood samples for DNA matches.

“It started me thinking about the process for recovering the missing in action or the unaccounted for in my own country,” she explained. While acknowledging the difference between the two cases—victims of genocide versus American service members lost in conflicts dating back to World War II—Wagner says both offered windows into the way societies mourn the missing. “There are similarities in how grief persists and the tensions around the ambiguity of not knowing what really happened to them,” she said. “It changes how you understand your past, your present and your future.”

Wagner quickly learned that identifying and repatriating war dead is a complex, time-consuming and expensive process. More than 1,600 soldiers are still listed as “unaccounted-for” from the Vietnam War alone, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency of the U.S. Department of Defense. Still, the remains of more than 1,000 Americans killed in Vietnam have been identified and returned to their families since 1973.

Spurred by pressure from families and veterans groups, the recovery efforts in part represent a reaction to the failures of the still-controversial war, Wagner said. “The government and the military are responding to families and veterans but also to current service members by saying: ‘This is the sacred obligation we have for those who die fighting for our country.’” Even the remains from the Vietnam crypt of the Tomb of the Unknowns in Arlington National Cemetery were disinterred in 1998 and DNA testing revealed the identity of its missing soldier—First Lieutenant Michael J. Blassie, an Air Force pilot shot down in southern Vietnam in 1972. “It was an act that signaled an important shift in forensic practice and the state’s means of commemorating its missing members of the military as individuals,” Wagner said.

Into the War Zone

Wagner believed she couldn’t truly approximate the plight of soldiers and their family without seeing the recovery process first-hand. With the JPAC team in central Vietnam, she joined the arduous effort to excavate the fatal helicopter crash site. Alongside dozens of Vietnamese laborers from nearby villages, the team cleared layers of thick jungle brush from the mountain crater. They carried dirt-filled buckets up the steep slope to a station where they sifted the debris through makeshift screens. For days, their efforts yielded only scraps of metal and munitions. Two discouraging weeks into their search, the team uncovered human teeth. Eventually remains recovered at the site led to the Wisconsin Marine’s homecoming.

“It changed the tenor of our mission,” Wagner said. “We were celebratory that we had recovered something after so much labor, but there was definitely a gravity to the moment. It was, in some ways, a somber achievement.”

Beyond the mission to Vietnam, Wagner continues to document missing service members’ stories, meeting with families and fellow veterans and visiting their hometowns. “They helped me understand the kinship a recovery engenders—from bringing a brother soldier home to finally being able to bury a loved one next to his parents,” Wagner noted.

To Wagner, the MIA research highlights the cultural and personal impact of anthropology—a message she conveys to her students. “I tell them that at the core of anthropology are real people’s lives,” she said. “As anthropologists, we go into communities and spend time trying to understand lived experiences. We tell people’s stories. And we have an obligation to do it right.”