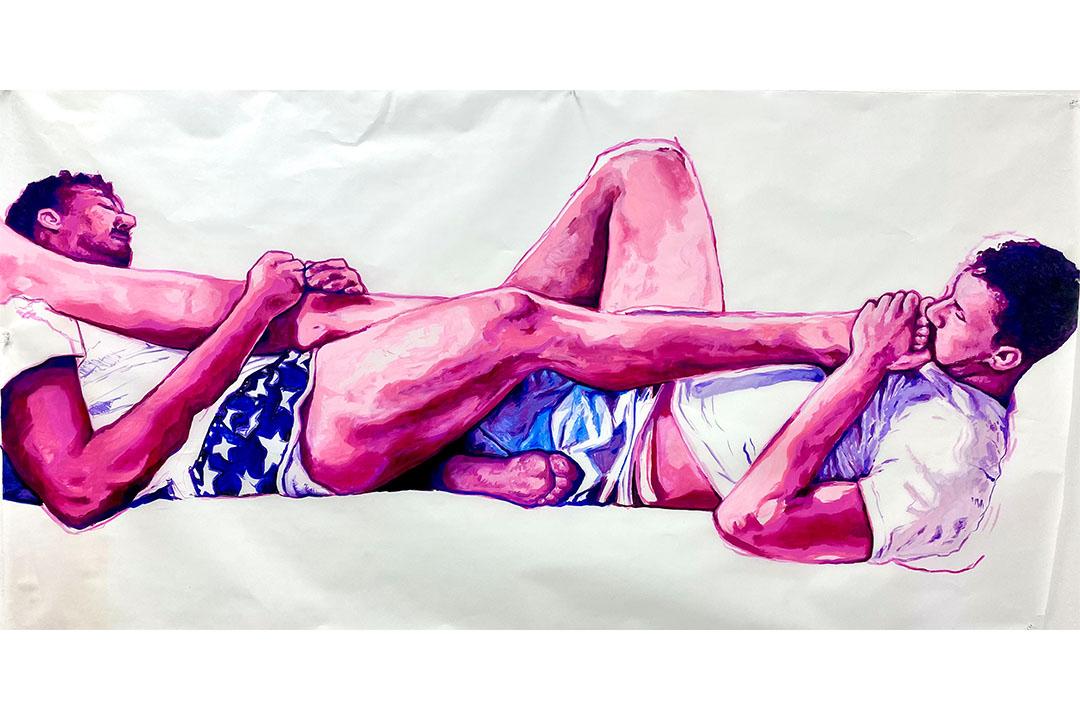

Artist Wes Holloway has a fascination with the physical. His art can depict grappling wrestlers, embracing lovers and bodies entangled in scenes of pleasure and pain.

Body images and the ways society responds to the human form is a theme that’s defined Holloway’s work—and his life. In 2003, as a freshman at the University of Texas, Holloway’s split-second decision to dive unknowingly into shallow water at a party had tragic consequences. He suffered a traumatic spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the chest down.

In many ways, the accident was a turning point for Holloway, a graduate student in Columbian College’s Social Practice Program, which connects art with policy and creative action through courses at the Corcoran School of the Arts & Design and the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration. He committed himself to pursuing his dreams of becoming a professional artist, while focusing his craft on deconstructing stereotypes of masculinity, sexuality and body ideals.

“As a man with a flawed body myself, I ask, ‘What is perfection, and what is truly beautiful?’” he said. “The beauty [of art] for me is presenting images that reflect the desire to want my body to do things—but also the acceptance that it doesn’t do those things anymore.”

A recipient of the Morris Louis Art Student Assistant Fund and the Martha Von Hirsh Memorial Scholarship, Holloway is grateful for the doors that opened to enable him to follow his interests in art and activism. “Attending GW puts me in a place where…I am able to effectively tie my artwork into the issues, with the hope that I will create meaningful change in viewpoints and legislature,” he said. “Complex problems demand creative strategies. These scholarships have given me the ability to uplift my voice.”

Holloway has exhibited his work in galleries from Texas to Nebraska to New York City, and taught art classes to underserved communities and others suffering from spinal cord injuries. (His thesis exhibition “Desiderium” will run at Gallery 102 through March 18.) He is a committed advocate for causes such as gay rights and accessibility issues, and sees his life and work as a conversation that helps him share his story and empathize with others.

“I can speak to people though art in ways that I can’t always do with words,” he said. “Art has helped open my eyes to what other people have lived through and the universality of what we all go through.”

"Attending GW puts me in a place...where I am able to effectively tie my artwork into the issues, with the hope that I will create meaningful change in viewpoints and legislature. ... These scholarships have given me the ability to uplift my voice."

Wes Holloway

Graduate Student, Social Practice Program

Growing up outside of Houston, Holloway always enjoyed drawing but was initially encouraged by his parents to seek a career in science. “They were not in favor of me going to school for art,” he laughed. “They told me I could study science or engineering or architecture—just not art.”

But after his accident, Holloway used art to help make sense of his new realities. Even as doctors explained the extent of his injuries—he had broken his C5-C6 vertebrae and would never regain use of his legs, abdomen or hands—he began experimenting with new ways of holding brushes and pencils in his wrists, while sketching images of bodies in motion. “At 18, I went from being an able-bodied young man to not,” he said. “It was quite the life shift and art has been my way of processing it.”

When he returned to school, Holloway was determined to dedicate himself to his art. “I told my parents that life’s too short and I’m going to follow this passion.” He originally considered becoming an art teacher, but his professors and mentors urged him to continue working in the studio. While still an undergraduate, Holloway won a spot at a Kennedy Center exhibition for young artists with disabilities. Even as he continued dealing with his limitations—his lack of hand functions prevents him from stretching his own canvases—he refined his artistic style. While painting remains his preferred medium, he’s experimented with collages, composite layers and superimposing images from popular media to challenge societal body representations.

“I consider [Holloway’s] work an intervention in the cultural blind spot that exists at the intersection of queer culture and the disabled body, reimagining those identities and proposing other worlds,” said Assistant Professor of Sculpture and Spatial Practices Maria del Carmen Montoya, who applauded Holloway for “deconstructing notions of perfection and prying open a space of possibility for the differently-abled body.”

Through nonprofits like the United Spinal Association of Houston and Art Reach in Texas, Holloway has led studio art programs for other people with disabilities as well as communities like senior citizens, children in foster care and victims of sex trafficking. “I think of art as a bridge building,” he said. “It can help us make common connections and gain a little bit of understanding of different people’s pasts and perspectives.”

Open Doors: The Centuries Initiative for Scholarships & Fellowships charts a course to increase access to the transformative power of a GW degree. Learn more about how GW is expanding opportunity for the next generation of leaders.