East meets West in Stephanie Travis’ Modern Architecture and Design Dean’s Seminar. As in: the East Building of the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art meets the West Building. It’s a face-off of design and philosophy—architect I.M. Pei’s modernist design for the East Building contrasted with John Russell Pope’s neoclassical style for the West. And the debate can get heated. In one corner you’ll find sociology major Kimmie Krane extolling the East’s soaring atrium and rigorously geometrical design. “I’m mesmerized by its open space and its triangular shapes,” she said. “In so many museums, you walk in and go right to the galleries. The East Building has a vastness that’s really beautiful.” But to Interior Architecture and Design (IAD) major Jamie Oakley, those avant-garde open spaces may be a little too vast. “I get lost walking around there,” he said. He’ll take the West Building’s domed rotunda and traditional halls any day. “I’m a lot more attracted to the classical look,” he noted.

Interlocking volumes, grid organization, movement, light, horizontality and transparency—these are some of the concepts explained, defended and even criticized in the freshman seminar taught by Travis, associate professor and director of the IAD Program. But before stepping into her classroom, many of her 18 students had never heard of these terms—let alone felt confident enough to use them in a debate. “Four months ago, those words weren’t in my vocabulary,” said Jason Katz, an urban development major from Columbian College’s Global Bachelor's Program. “Before this class, I’d never looked twice at a building. Now I notice the design of the sprinkler systems.”

Utilities blueprints may not have been on Travis’ curriculum when she created the course, which like other Dean’s Seminars, offers small classes on concentrated topics. But opening students’ eyes to architecture is exactly what she was hoping for. From pre-meds and psychology majors to future architects and fine arts students, Travis’ class serves as an introduction to modern architecture and design through the context of key buildings of the 20th century. Most students begin the course with little knowledge of floor plans and design concepts—and leave with a new appreciation for the buildings that dot their daily landscapes.

“Architecture is all around us. We confront great buildings every day,” Travis said. “I don’t want my students to walk around oblivious to the buildings they pass. I want them to be able to identify the concepts they see and to understand and explain them.”

‘Everything Connects’

As an architect rather than an historian, Travis was determined that her seminar would avoid history class tropes like memorizing dates and cities. “When I took architecture history, it was about viewing slide after slide after slide,” she recalled. Through participation-heavy lectures, classroom games and dynamic debates on topics like building heights and furniture knock-offs, Travis instills basic design concepts while providing a background in modern masters and their work. The class culminates in field trips to D.C. landmarks including Philip Johnson’s Kreeger Museum, Gordon Bunshaft’s Hirshhorn and Pei’s East Building.

Travis encourages the students to look at each building like an architecture critic for The Washington Post. She asks them to go beyond a subjective opinion on whether they like or don’t like a building and look deeper into aspects such as the structure’s form meeting its function. “Architects don’t just design a building because they like it,” Travis said. “There’s an underlying concept to everything—how a building connects to nature, to a city grid, to local material. None of it is an accident. As Charles Eames said, ‘Everything connects.’ That is true of this course too!”

Like other non-IAD students, political science major Bailee Weisz enrolled in the seminar as an adventure, a chance to explore a subject outside of her comfort zone. At the beginning of the semester, merely familiarizing herself with architectural terms was intimidating. “There was a lot of information on topics I’d never heard of, like symmetry and geometry and how you move through spaces,” she said.

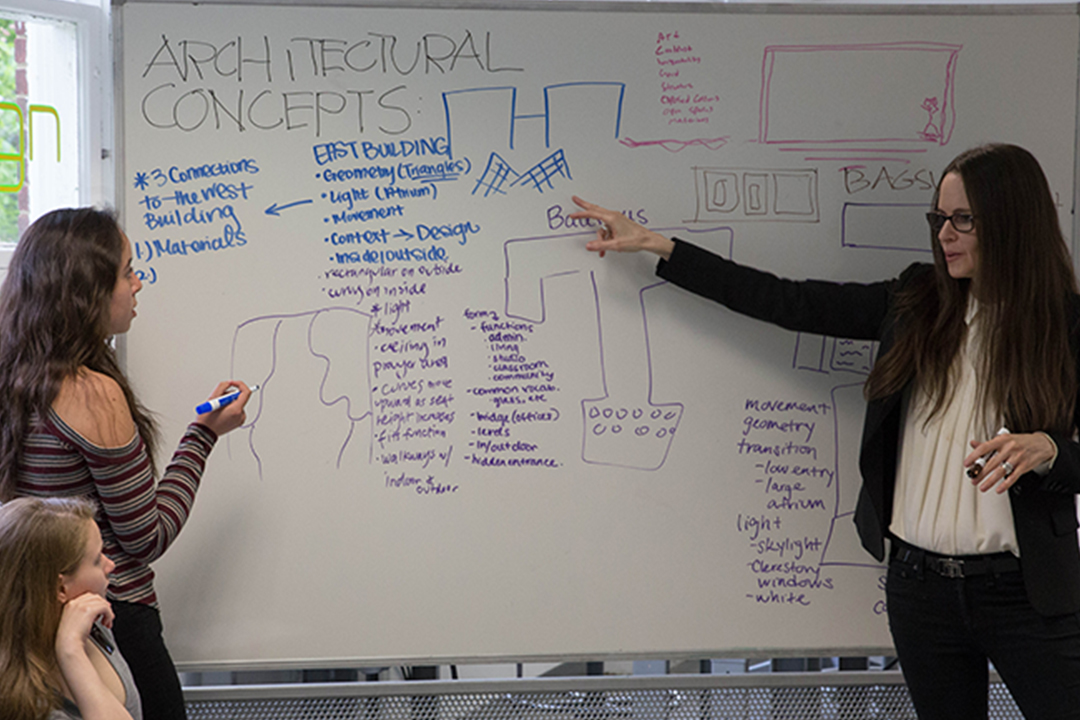

Stephanie Travis' (foreground) in class with freshmen (left to right) Jamie Oakley, Jason Katz, Bailee Weisz and Kimmie Krane

As the class progressed, Travis’ students gained the confidence to train a critical eye on architectural masterpieces. “She gave me a grasp of how to approach a building and sound like I know what I’m talking about!” Weisz said. By the end of the semester, the political science student wasn’t shy about critiquing modernist icon Le Corbusier’s austere designs, like his Marseille housing project Unité d'habitation. “It looks like a big concrete jail cell,” she said. Katz, who had barely noticed buildings before, now declares Phillip Johnson’s Glass House a “masterpiece,” but dismisses his Crystal Cathedral as “atrocious." The class, he said, "has made me more critical but not more judgmental.”

Likewise, Travis is comfortable confiding a blasphemous architectural opinion: “Frank Lloyd Wright is really not my favorite,” she laughed. While she concedes that Wright, perhaps the world’s best-known architect, is “a genius,” she prefers, for example, the Hirshhorn’s open cylinder and courtyard fountain. Her assessment may leave some scholars shaking their heads, but her seminar students learn that even a controversial claim can be defended.

“Whether or not they pursue the study of interior architecture and design, analyzing these designs and articulating what works and what doesn’t is an exercise in critical thinking,” she said. “That skill will make them stronger designers—or just stronger thinkers.”