In early March, the emergency department at New York–Presbyterian Queens Hospital was abuzz with stories of coronavirus outbreaks from China to Italy. Dr. Luke Fey, BS ’13, heard rumors of overrun emergency rooms and ventilator shortages. But each morning brought a busy new patient-load to his ER, and little chance to stop and think about a virus on the other side of the world. “To be honest, it didn't feel real to me,” said Fey, a third-year emergency medicine resident.

Just a few weeks later New York City would become the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, and Fey, along with healthcare workers across the country, would be on the frontlines of a global crisis. From the middle of March through early April, Fey’s emergency room was inundated with dozens of coronavirus cases each day. With patients lining the ER hallways, he spent 12-hour shifts racing from 20-year-old’s doubled over with cough and fever to senior citizens wheezing into oxygen tanks.

“Every day wore you down—emotionally, physically, mentally,” he said. “I never thought I’d see anything like it.”

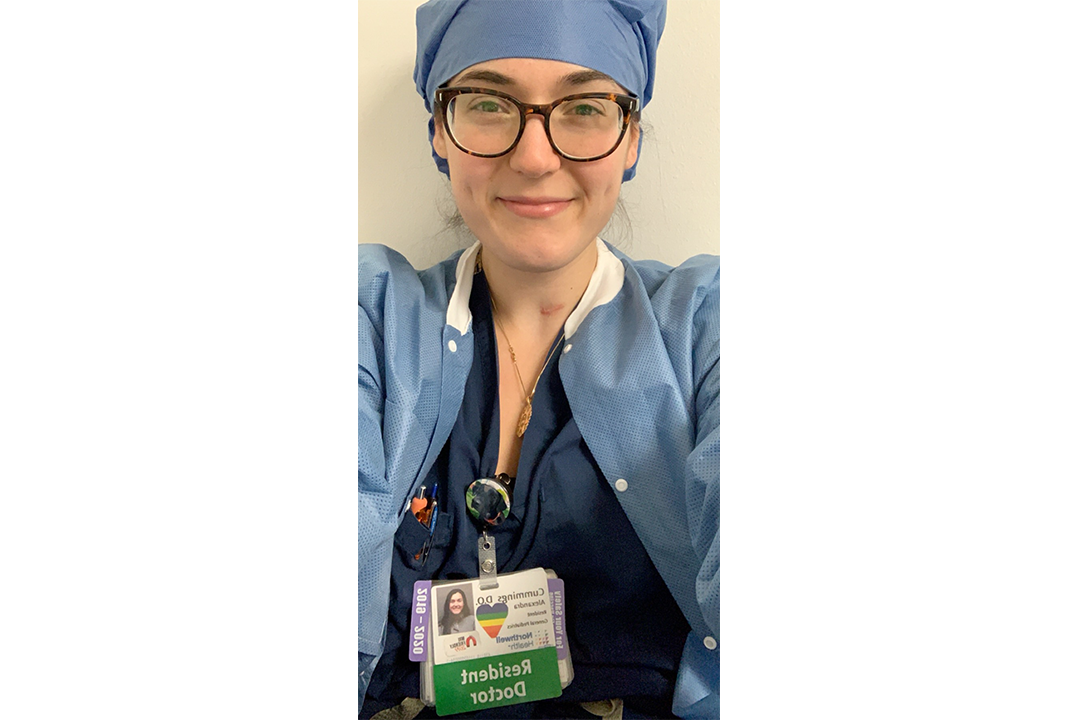

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital staffs around the world have struggled to keep up with waves of patients and shortages of supplies—all while putting aside fears for their own safety. “We’ve rallied together to fight the virus,” said Dr. Alexandra Cummings, BS ’14, a pediatric resident at Cohen Children's Medical Center on Long Island. “This is something we’ll remember forever and—cross your fingers—never face again.”

At the pandemic’s peak in New York City, Fey said his ER was a non-stop crisis zone. “We were at the point where pretty much everyone coming in had coronavirus—and they didn’t stop coming,” he said. As beds filled rapidly, his hospital converted spare space from the cafeteria to the ORs into COVID wards. Still, the overcrowded ER was treating three times its patient capacity. Fey’s team never experienced an extreme ventilator shortage, but they quickly realized that intubating the sickest patients wasn’t always effective. “They weren’t getting any better,” he said. “If you ended up on a ventilator, you had a very high mortality rate.”

Dr. Alexandra Cummings, BS ’14, is a pediatric resident at Cohen Children's Medical Center on Long Island.

In the hospital parking lot, refrigerated tractor trailers served as make-shift morgues as Fey held emotional conversations with families. He watched critical patients send FaceTime goodbyes to their families and escorted an elderly woman through the locked-down ER for a final visit with her husband. “I can keep it together with my patients. But seeing what the families go through hit me hard,” he said.

Even non-emergency hospital workers were recruited into COVID care. At Cohen, Cummings’ pediatric colleagues were deployed to help care for COVID patients in other areas of the hospital as she helped convert her units into coronavirus centers. “There's literally no part of the hospital that isn't accommodating COVID patients,” she said. Postpartum mothers and newborns were moved to a separate building. But with many other New York hospitals closing their labor and delivery units, more pregnant women were diverted to Cohen. Mothers who tested positive for COVID could room with their babies if they were asymptotic. But women with more severe symptoms were separated from their newborns. “It’s heartbreaking for a new mom to miss that first physical bonding with her baby,” Cummings said.

For now, Fey hopes the worst has passed. Patient volume has eased from an onrush to a steady stream. He and his colleague are working eight-hour shifts instead of 12-hour marathons. After a brief shortage of personal protection equipment, he now has a surplus of supplies, from donated 3D-printed face shields to the N95 masks that he rarely takes off—and that have left a rash of blisters across his nose.

“I feel rejuvenated because we seem to be on the other side,” Fey said. Still, he worries about people rushing too quickly back to their lives, potentially triggering another wave of infections. “But will it be as bad? That’s something none of us want to think about right now.”