Biology professor, former graduate student part of international project

An international team that included Columbian College Professor James Clark and his former graduate student Brian Andres, MS ’03, has discovered and named the earliest and most primitive pterodactyloid—a group of flying reptiles that are the largest flying creatures to have ever existed. The team also established these reptiles flew above the earth some 163 million years ago, longer than previously known.

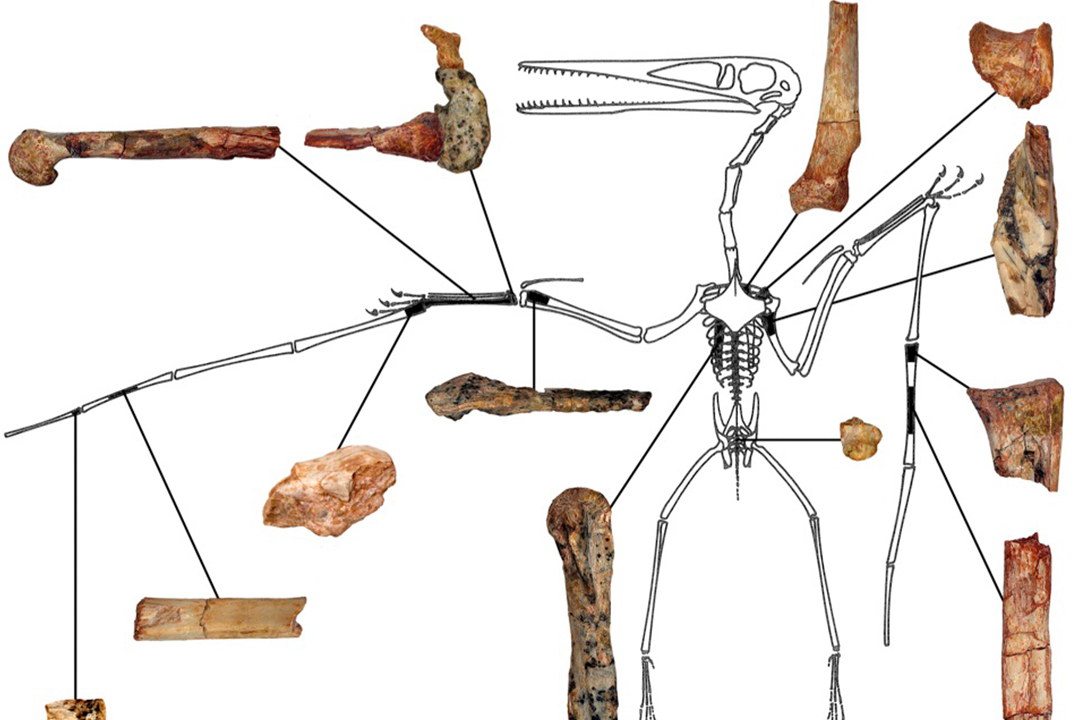

Working from a fossil discovered in northwest China, the project— led by Clark, Andres (now a University of South Florida paleontologist), and Xu Xing of the Chinese Academy of Sciences—named the new pterosaur species Kryptodrakon progenitor and established it as the first pterosaur to bear the characteristics of the Pterodactyloidea. (The flying reptile would become the dominant winged creatures of the prehistoric world.) The team’s findings were published last month in the journal Current Biology.

“This finding represents the earliest and most primitive pterodactyloid pterosaur, a flying reptile in a highly specialized group that includes the largest flying organisms,” said Chris Liu, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Earth Sciences. “The research has extended the fossil record of pterodactyloids by at least five million years to the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary about 163 million years ago.”

Kryptodrakon progenitor lived around the time of the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary. By studying the fossil fragments, researchers also determined that the pterodactyloids originated and evolved in terrestrial environments rather than marine environments where other specimens have been found.

The fossil is of a small pterodactyloid with a wingspan estimate of about 4.5 feet. Pterodactyloids—who went on to evolve into giant creatures, some as big as small planes—became extinct with the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Pterosaurs are considered close relatives to the dinosaurs, but are not dinosaurs themselves.

The discovery provides new information on the evolution of pterodactyloids, said Andres. The area where the fossil was discovered was likely a flood plain but as the pterosaurs evolved, their wings changed from being narrow, which is more useful in marine environments, to being more broad to help in navigate land environments.

“He (Kryptodrakon progenitor) fills in a very important gap in the history of pterosaurs,” said Andres. “With him, they could walk and fly in whole new ways.”

The fossil that became the centerpiece of the research was discovered in 2001 by Chris Sloan, formerly of National Geographic and now president of Science Visualization. It was found in a mudstone of the Shishugou Formation of northwest China on an expedition led by Xu, Clark, and Andres (Clark’s graduate student at the time). The desolate and harsh environment has become known to scientists worldwide as having “dinosaur death pits” for the quicksand in the area that trapped an extraordinary range of prehistoric creatures, stacking them on top of each other, including one of the oldest tyrannosaurs, Guanlong. Kryptodrakon progenitor was found 35 meters below an ash bed that has been dated back to more than 161 million years.

The specimen is housed at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China. The name Kryptodrakon progenitor comes from Krypto (hidden) and drakon (serpent), referring to “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” filmed near where the species was discovered, and progenitor (ancestral or first-born), referring to its status as the earliest pterodactyloid.

"Kryptodrakon is the second pterosaur species we've discovered in the Shishugou Formation and deepens our understanding of this unusually diverse Jurassic ecosystem,” said Clark, a Ronald B. Weintraub Professor of Biology at Columbian College. “It is rare for small, delicate fossils to be preserved in Jurassic terrestrial deposits, and the Shishugou fauna is giving us a glimpse of what was living alongside the behemoths like Mamenchisaurus."

The specimen is now housed at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China.

Pictured above: (Top) The preserved bones of Kryptodrakon progenitor (shown here in different views) have yielded new discoveries on the origin of the pterodactyloids. Illustration by Brian Andres. (Bottom) The remote Shishugou Formation in northwest China is a hot-bed for the discovery of dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and other prehistoric remains. The fossil that forms the centerpiece of the pterodactyloid pterosaurs research was found in the red mudstone shown here. Photo by James Clark.