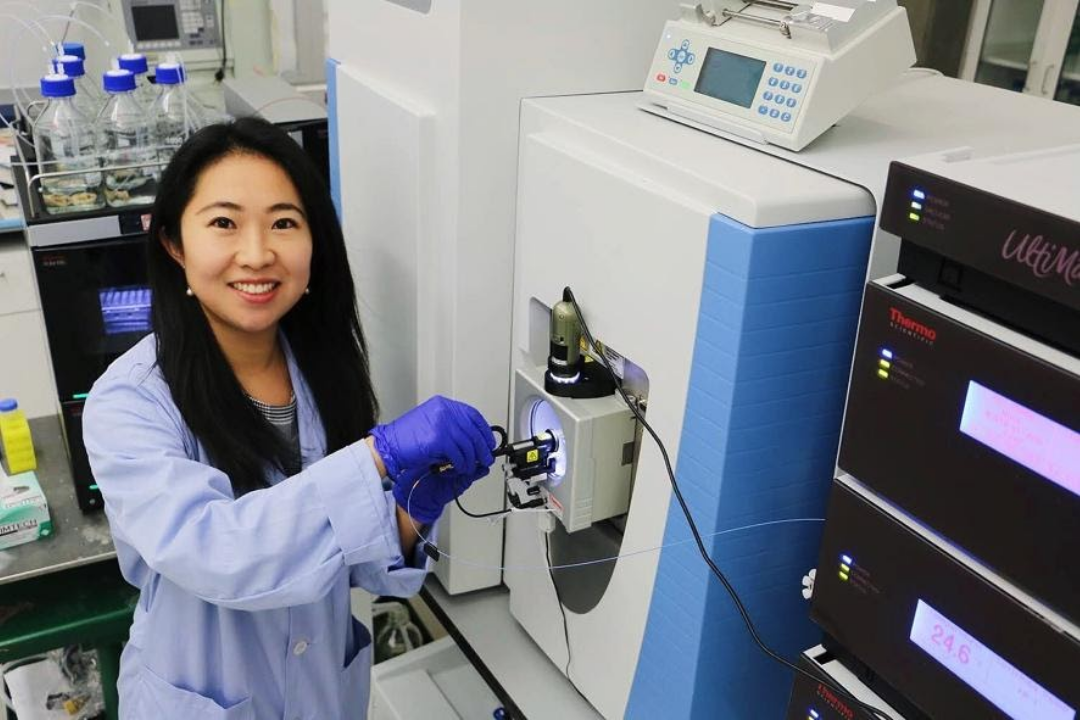

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, junior Jessica Huang—a chemistry minor in GW’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences—conducted scientific experiments using state-of-the-art equipment at Science and Engineering Hall (SEH).

But this spring, when testing the pH range of an acid, she turned to some less-traditional tools: a cabbage, a bottle of vinegar and plastic cups and spoons. And her setting wasn’t a world-class science lab. It was her kitchen in Pittsburgh.

With COVID-19 limiting access to campus resources, Assistant Professors of Chemistry LaKeisha McClary and Ling Hao took their Introductory Quantitative Analysis Laboratory class back to basics—and gave new meaning to the term “kitchen chemistry.” They redesigned the class to help students transform their independent research assignments into do-it-yourself remote experiments, substituting household products for lab equipment and vinegar and baking soda for chemicals and solutions.

“Remote learning certainly challenged students and faculty alike, and perhaps even more so when it came to laboratory experiences,” said Chemistry Department Chair Christopher Cahill, a professor of chemistry and international affairs. “Each of our laboratory faculty stepped up in terms of creativity and accessibility—and Professors McClary and Hao deserve an extra nod for cultivating ‘do-it-yourself’ projects that could be done in one’s kitchen at home.”

The heart of the laboratory course is what McClary referred to as an “authentic research experience,” a start-to-finish independent experiment that the 20 students—mostly chemistry majors and minors—perform in small groups. Students design a 2- to 3-week original experiment based on their own research. They analyze and interpret their findings and write a peer-reviewed style paper using a professional chemistry journal’s template.

But when the university transitioned to remote learning, McClary and Hao, like many other faculty members, were forced to adapt their curriculum. They replaced the course’s in-class group experiment with a remote lab bench that simulated scientific techniques, like mixing virtual chemicals in online beakers. But in fall 2020, the authentic research experience initially transitioned from a hands-on project to a “thought experiment,” McClary said.

“The students designed the experiment and predicted what they thought might happen,” she said. “But they didn’t do the actual experiment.”

Assistant Professor of Chemistry LaKeisha McClary

This spring, the two professors were determined to restore the independent experiment. Adapting a Journal of Chemical Education article, they introduced do-it-yourself components that could be performed at home with inexpensive materials and nonhazardous chemicals. From her apartment near campus, senior chemistry minor Sydney Cohen tested the acid content of white wine vinegar using a pH indicator made from boiled red cabbage, which contains a pigment that changes color when mixed with an acid or a base. Building on her COVID experiences, senior neuroscience major and chemistry minor Emily Hannah borrowed bottles of hand sanitizers from friends and family to measure their alcohol concentration and determine their post-expiration date efficacy. “This is definitely unconventional compared to in-person labs I have completed,” Hannah said, “but it gave us the freedom and independence to pool our resources and devise a project that truly had real-world applications.”

“As scientists we are used to having access to all of the equipment, chemicals, safety materials and teaching resources that we need,” said senior chemistry major Elliot Heywood. “I thought the experiments were a great way to substitute for a traditional laboratory experience during the pandemic.”

While the at-home experiments couldn’t replace the quality and precision of campus labs, Hao said it forced the students to find resilient ways to cope with less than ideal circumstances. “The positive thing you can gain from virtual and at-home labs compared to actually working in SEH is that students have to be more independent,” she said.

The assignment also involved acknowledging limitations. Hao had her students conduct error analysis and evaluate possible causes of experimental variations—like imprecise measurements on kitchen scales and the failure to reproduce exact results in multiple at-home trials.

“We know [at-home experiments] won't get as accurate results as in the lab. But I tell my students that’s part of science,” she said. “In any setting, it is absolutely normal for an experiment not to work the first time.”

The course, which is part of the Writing in the Disciplines (WID) program, requires students to defend their experiments in journal-quality papers. They also participate in peer-reviews and a mock editorial board meeting to learn how academic journals review submissions. In 2020, the do-it-yourself module received the WID Best Assignment Design Award.

While the professors say they welcome a return to SEH, the at-home experiments taught them lessons about engaging students and helping them hone their lab skills—even from their kitchens. “I think it gave them a sense of ownership,” McClary said, “and showed them how science connects to the real world—wherever that is for them right now.”