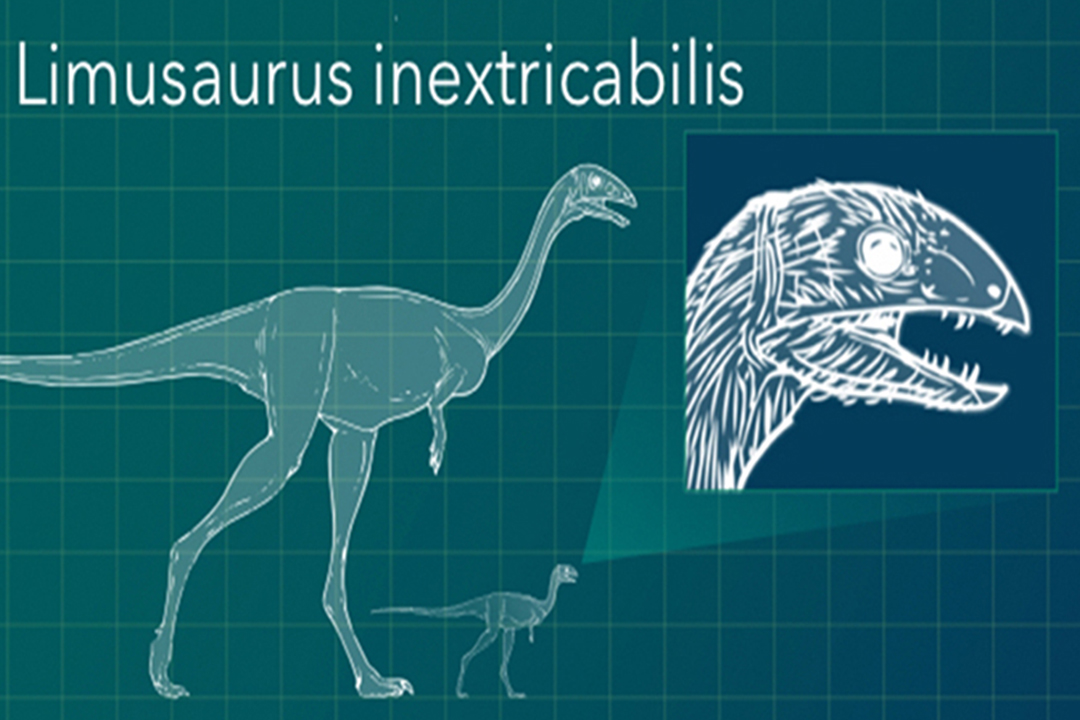

A study co-authored by Ronald Weintraub Professor of Biology James Clark, discovered a new species of dinosaur, Limusaurus inextricabilis, that lost its teeth in adolescence and did not grow another set as adults. The finding, published in the journal Current Biology, is a radical change in anatomy during a lifespan. It could offer insight on how birds evolved from dinosaurs, and explain why birds have beaks but no teeth.

The research team studied 19 Limusaurus skeletons discovered in ancient “death traps” where they became stuck in mud and died in the Xinjiang province of China. The dinosaurs ranged in age from babies to adult, showing the pattern of tooth loss over time. The baby skeleton had small, sharp teeth, and the adult skeletons were consistently toothless.

“This discovery is important for two reasons,” Clark said. “First, it’s very rare to find a growth series from baby to adult dinosaurs. Second, this unusually dramatic change in anatomy suggests there was a big shift in Limusaurus’ diet from adolescence to adulthood.”

Limusaurus is part of the theropod group of dinosaurs, the evolutionary ancestors of birds. In earlier Limusaurus research, Clark’s team described the species’ hand development, noting that the dinosaur’s reduced first finger may have been transitional and that later theropods lost the first and fifth fingers. Similarly, bird hands consist of the equivalent of a human’s second, third and fourth fingers.

These fossils indicate that young Limusaurus could have been carnivores or omnivores while the adults were herbivores, as they would have needed teeth to chew meat but not plants. Chemical makeup in the fossils’ bones supports the theory of a change in diet between babies and adults. The fossils also could help to show how theropods such as birds lost their teeth, initially through changes during their development from babies to adults.

“For most dinosaur species we have few specimens and a very incomplete understanding of their developmental biology,” said Josef Stiegler, a biology graduate student who co-authored the study. “The large sample size of Limusaurus allowed us to use several lines of evidence including the morphology, microstructure and stable isotopic composition of the fossil bones to understand developmental and dietary changes in this animal.”

The research, which was funded by a National Science Foundation grant, was performed by Stiegler and Shuo Wang of China’s Capital Normal University under the guidance of Clark and Dr. Xu Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.