It’s a tale of two Siberian cities: one prospering, the other fallen on hard times, both surrounded by an Arctic tundra of thawing permafrost and fading glaciers. In the shadow of the Ural Mountains, these twin towns—the gas-and-oil rich Salekhard and the coal-starved Vorkuta—have become a living laboratory for studying the affects of climate change on both people and the environment.

And for a month this summer, Salekhard and Vorkuta were home to two GW geography professors (Assistant Professor of Geography and International Affairs Dmitry Streletskiy and Associate Professor of Geography Nikolay Shiklomanov) and eight students, along with their peers from the United States, Russia and European Union. The Siberian cities provided an ideal landscape for examining the links between human and physical geography at a ground zero for global warming.

“The Arctic is dynamic. In terms of climate change, it sees all the challenges that cities around the world are facing but at a quickened pace,” said Luis Suter, a second-year geography graduate student and research assistant for Streletskiy. “Most people think ‘Arctic’ and picture polar bears and glaciers, but the people up there are grappling with questions of infrastructure and urban planning too. We wanted to expose students to the real Arctic life.”

The cohort of GW students were participants in a course led by Streletskiy called International Arctic Field Course on Permafrost & Northern Studies. The fieldwork conducted for the course was funded, in part, through a $3 million grant from the National Science Foundation, which established the GW-based Arctic PIRE program—a cross-disciplinary coalition of geographers, political scientists and migration experts tasked with looking at environmental issues, such as thawing permafrost, as well as social factors, including economic and labor cycles. Ultimately, the researchers plan to develop an Arctic Urban Sustainability Index to assess the health of Arctic cities and the consequences of human activities in the region.

For his course, Streletskiy incorporated PIRE themes like international collaboration, permafrost measurements, boom-bust economic cycles and the influx of migrant workers into Arctic cities—all staples of modern geography research. “Today, physical geography projects also involve a social component,” he said

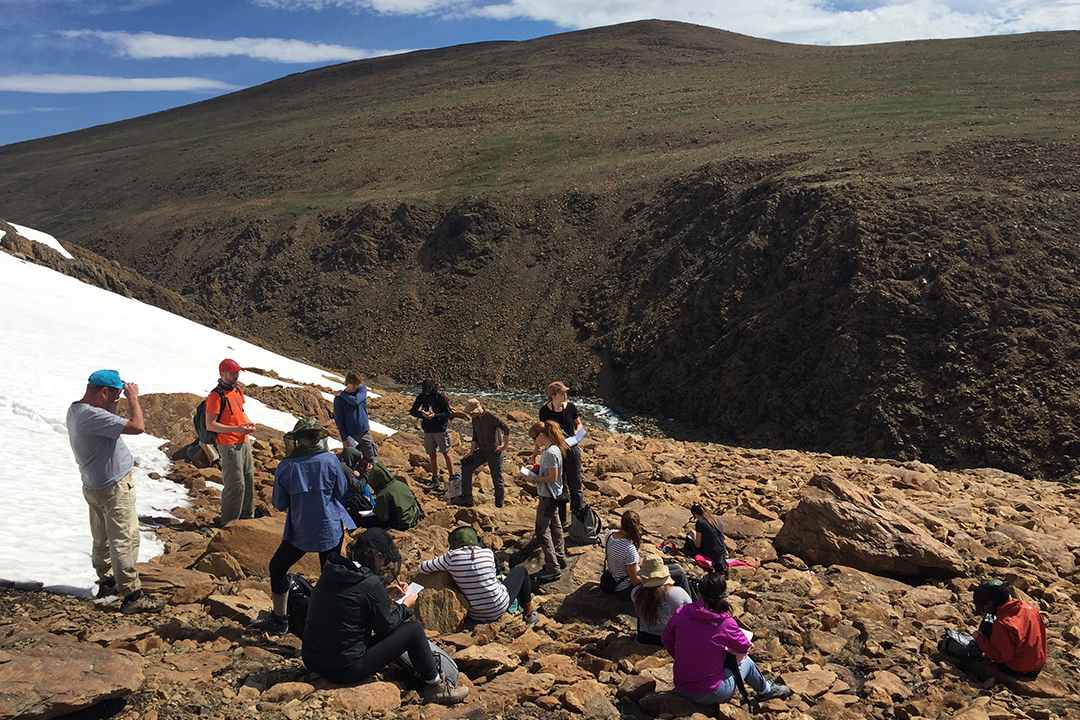

Melting glacial landscape in the Rai-Iz Valley along the Polar Urals. (Photo: Anna Sumi for PlanetForward.org)

The Journey to Siberia

The trip began in early July with a 40-hour train ride along the thousand-mile route from Moscow to Western Siberia. Partnering with faculty and undergraduates from Moscow State University, the GW students acclimated themselves to conditions that ranged from the 24-hour daylight of the Siberian summer to a 90-degree heatwave and swarms of mosquitoes. “Our train brought us into the starkness of polar day,” said Claire Franco, a junior double majoring in geography and international affairs. “We wouldn’t see nighttime hours of darkness until almost a month later.”

After two days crammed into un-airconditioned train cars, the group arrived in Salekhard, a 50,000-population oil- and gas-producing city. The city has recently suffered from the fall in global energy prices, but, Suter said, evidence of its prosperity can still be found on nearly every corner, from construction projects to rows of hotels and churches. Two weeks later, the students arrived in Vorkuta, a once-bustling coal-mining town now languishing under the effects of the industry’s downward spiral. “Vorkuta is like Detroit, but with fewer foreclosed homes and more half-empty apartment houses,” Suter said. “The two cities provide a stark contrast.”

A tale of two cities: A new apartment complex in Salekhard (left). Old Soviet-style apartment blocks in central Vorkuta (right). (Photos: Luis Suter)

Through meetings with local officials—museum managers, city planners, geologists, architects—the students learned first hand about the challenges of managing urban sustainability in severe climates. For example, urban infrastructure is mainly built on foundational pilings driven into permafrost. The warming permafrost causes structural damage to buildings, pipelines and roads. “These failures impact people's quality of life and economic prospects,” Suter explained.

The group combined their urban study with fieldwork in the surrounding tundra to record climate change’s impact on the landscape. In the Rai-Iz Valley, they observed the remnants of one of the last three remaining glaciers that once dotted the Polar Urals. In the foothills of the Yamalo-Nenets region, they measured permafrost characteristics while swatting away clouds of mosquitoes in the punishing late summer sun. “I finally got to try out my field skills and put all those years of studying climate change and sustainability to use,” said Nina Feldman, BA ’17, now a first-year geography graduate student. “But another very important lesson I took away from this trip is that there are a lot of mosquitos in the Arctic, so bring bug spray. Lots and lots of bug spray.”

Students conducting fieldwork in the tundra outside of Labytnangi, Russia. (Photo: Anna Sumi for PlanetForward.org)

For Feldman, the trip also combined international study with a personal connection. “My parents are originally from Russia, and going back to see the country they grew up in has been a life-long dream of mine,” she said. “I felt like I was reconnecting with my family's heritage.” She also bonded with her peers from Moscow State on the long hot train ride—even when they didn’t speak the same language. “For 40 hours, we exchanged stories, played card games, admired the landscapes and just enjoyed each other's company. At times there was a language barrier, but it didn't seem to matter at all.”

The program continues next summer in America when Streletskiy will take a cohort of GW students and Moscow State undergraduates to Alaska. “One of the most important things our students can learn is how to work with their international counterparts in a multinational language environment,” he said. “This is a collaborative field. Out in the tundra, nationalities and ideologies disappear. Everybody works together.”

GW students alongside students from Moscow State University. (Photo: Luis Suter)