What is a ghetto? A racially-segregated city block? An enclave of immigrants? A walled urban prison? The ideologically charged term defies easy definition. It can be a noun or an adjective. It can refer to a physical place or a concept. And while the word comes from the Italian “gettare” for “casting,” it has at times been linked to the Yiddish “gehektes,” meaning “enclosed,” and the Latin “Giudaicetum”—“Jewish.”

In his book Ghetto: The History of a Word (Harvard University Press, 2019), Daniel Schwartz, associate professor of history and director of Columbian College’s Judaic Studies Program, doesn’t try to settle on a dictionary definition of “ghetto.” He’s interested in tracing the historical path of the word—from the segregated Jewish quarter of 16th century Venice to the Nazi holding-pens of Eastern Europe to the streets of New York’s Lower East Side. “I thought of researching the book as riding a raft down a river and seeing where it took me,” he said.

The journey was more than a lesson in linguistics. Schwartz spent six years following the controversial word’s footprints, combing through historical texts, digital archives and his own original research. Each reference gave him a window into the shifting nature of cultural identities. Whether associated with Jews, immigrants or African Americans, “ghetto” has evolved through history. “Depending on how it’s defined and who gets to define it,” Schwartz said, it has stood for both oppression and resilience, a sign of segregation and a badge of authenticity, a symbol of bigotry and a synonym for home.

“The history of the ghetto is also the history of the struggle over a word and the attempts to figure out what exactly it means,” Schwartz said.

From Europe to the U.S.

Schwartz warns against making generalizations about ghettos. But at its most basic level, the terms usually applies to sections of cities where minority groups are confined by segregation policies, physical barriers or socioeconomic factors such as restricted educational opportunities or low-paying jobs.

The first use of the word “ghetto” was in Venice, Italy, in 1516. The city’s Jews were required by law to reside in just a few small blocks. (The ghetto was near what had been the city’s copper foundry, hence the Italian derivation of the word for “casting” and the Venetian term “getto” for “foundry.”) In the 16th and 17th centuries, cities like Venice and Rome forcibly segregated their Jewish populations, often walling them off and submitting them to a set of restrictions. In the late 19th century, the word crossed the Atlantic Ocean, settling into immigrant-heavy areas like New York’s Lower East Side and Chicago’s Near West Side. Immigrants weren’t legally mandated to live in these densely-packed districts, but they were often trapped by discrimination in housing and hiring. Framed by factories and docks, author Jack London called them “working-class ghettos.”

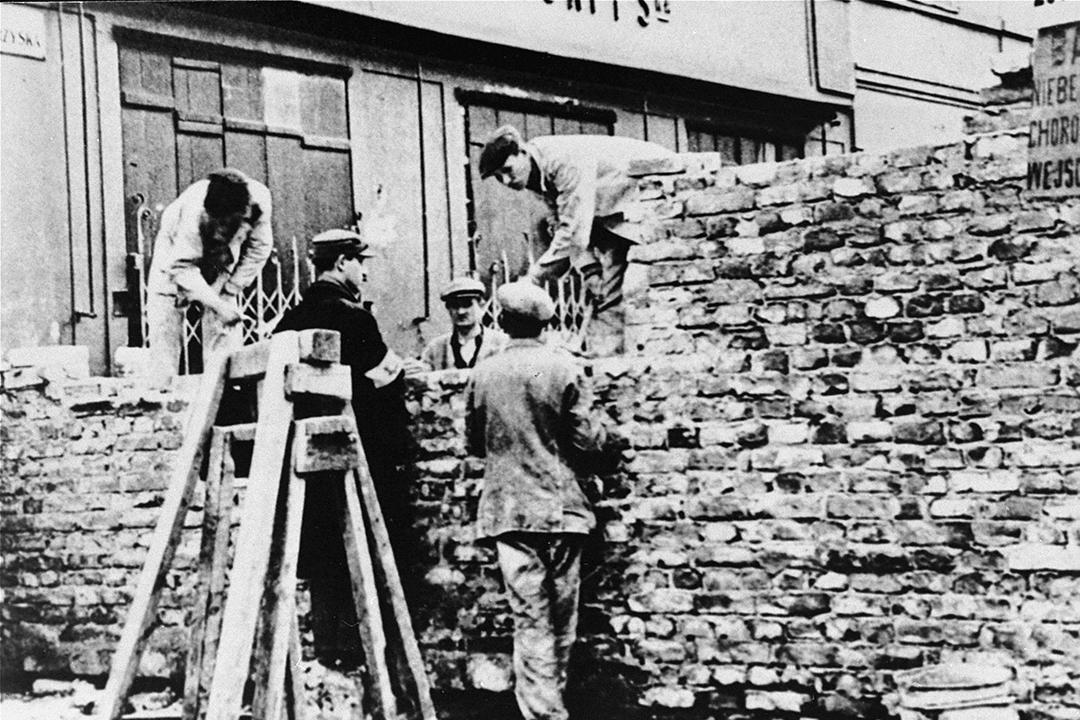

Back in Europe, “ghetto” was appropriated for the desolate sections of Nazi-occupied cities where Jews were held before being shipped to death camps. Today, Schwartz said, the word is probably most associated with impoverished inner-city African American neighborhoods.

Throughout the word’s history, “it has had mostly negative connotations,” Schwartz said. “It’s often associated with overcrowding, poverty and racial and religious segregation. When most of us think of ghettos, we picture people confined in dilapidated conditions against their will.”

A Source of Pain and Pride

As Schwartz delved deeply into the shifting meanings of "ghetto," he has also made the case for a more nuanced understanding of the word. Yes, “ghetto” can draw a roadmap of historical persecution, he noted. But it has also, at times, celebrated a culture’s strength, from its shared heritage to its social and artistic triumphs.

The crowded Lower East Side of the early 20th century, for example, was rife with disease. Its packed tenements were prime sources of fire deaths. Still, the Jews who settled there established synagogues, libraries and Jewish-owned businesses. “People have sometimes looked at the ghetto not as a prison but as a fortress, a place of security, a place that represents home, however modest it may be,” Schwartz said. Harlem’s ghetto was the setting for the 1920s artistic renaissance with writers like Langston Hughes and musicians like Billie Holiday. Even the notorious Warsaw ghetto of Nazi-occupied Poland is remembered for the doomed Jewish resistance fighters who staged a courageous uprising in 1943 against overwhelming odds.

Schwartz also dissected the use of “ghetto” in slang and pop culture, reflecting its pull between poverty and pride. “Ghetto” can be a dehumanizing insult, as in “being ghetto” which usually means behaving in a low-class manner. But other slang terms such as “ghetto fabulous” or “ghetto chic” convey a flashy glamour. “You can see the double-edged nature of the word,” Schwartz said. “It can be something that is low-quality but also something that has a flamboyant high quality.”

In past semesters, Schwartz has taught an undergraduate course on the ghetto as a concept. As in his book, Schwartz resisted handing his students an easy definition. He opened his class by asking them to call out terms they associated with the word. Many responded with “poverty,” “segregation” or “crime.” By the end of the class and by the end of his book, his students and readers often discover a wider array of words. Both, Schwartz says, are generally “surprised to learn the history of some of the more positive understandings of the term.” As a word, “ghetto,” can tell the story of centuries of people and places, Schwartz said. “Depending on who uses it and how it’s used, it’s a word that keeps telling stories today.”