The unfortunate reality of chemistry is that chemists, in their quest to innovate and devise new products to meet societal demands, sometimes create chemicals that are toxic. Look no further than some of the chemicals found in paint, glue, and even cosmetics. Some, like dioxins, are highly toxic to many animal species and are ending up as far away as the North Pole.

Enter green chemistry advocate Adelina Voutchkova, who joined Columbian College last year as an assistant professor of chemistry.

“Chemists are very skilled at making new molecules to serve a particular function, but most are not trained to consider the unintended long-term effects of those chemicals on humans and other animals,” said Voutchkova. “We are taking a different, less traditional approach.”

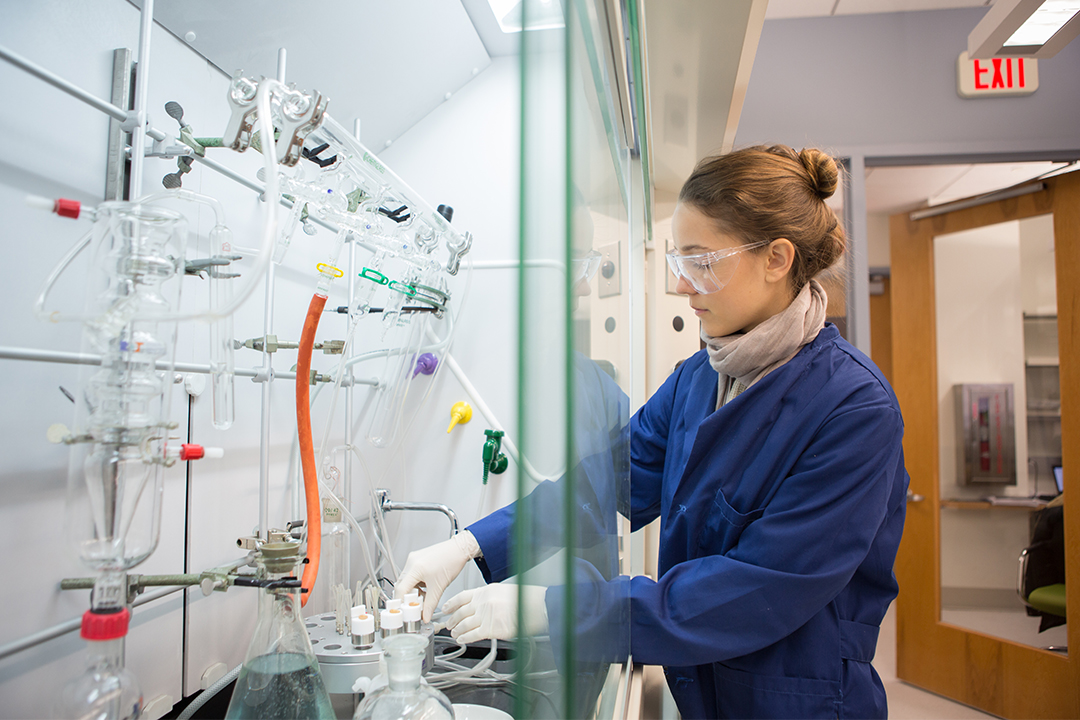

With a research team of both undergraduate and graduate students, Voutchkova is exploring ways to design safe chemicals that are biodegradable and not harmful to mammals. It is a two-pronged effort that includes developing new chemical methodology to synthesize chemicals with reduced environmental impact, and creating tools for chemists to devise chemicals with minimal biological activity.

Research into green chemistry began with Paul Anastas, whom Voutchkova studied under at Yale University. He and colleague John Warner founded the field in the early 1990s. Voutchkova is now at the forefront in pioneering the movement to design safer and more effective chemicals, a sub-field of green chemistry. Voutchkova, Anastas, and EPA scientist Robert Boethling co-edited a handbook on the topic, and Voutchkova and Anastas are currently writing an educational resource publication titled Toxicology for Chemists, geared toward undergraduate students.

“My collaborators and I are trying to change the way chemists design commercial chemicals,” said Voutchkova. “Mammals and fish experience severely negative effects, such as infertility, from certain chemicals. But it’s very difficult to design chemicals to be biodegradable and non-toxic. Chemists traditionally are not trained to think about this.”

One aspect of her research is focused on chemicals similar to Bisphenol A (BPA), which was used in baby bottles and many other household products. In 2010, the FDA warned that BPA can have a disruptive effect on hormones in both humans and wildlife.

“We would like to figure out what makes BPA an endocrine disruptor to avoid making the same mistake again,” Voutchkova said.

Farid Van Der Mei, a senior undergraduate student majoring in chemistry and mathematics, and Nan An, a chemistry graduate student, are working with Voutchkova to develop guidelines for green chemical design to encourage other chemists to think about toxicity of chemicals when designing molecules. The effort could make determining toxicity much less expensive and time intensive.

“If this works, it could change everything,” said Van Der Mei. “You would know if a chemical was toxic by evaluating the structure instead of having to test it. To get the private sector to adopt green chemistry, you have to make it cost effective and this would do that.”

Voutchkova is eager to pass on the culture of green chemistry to others. “We have the opportunity to make a difference by choosing what we teach our students about chemistry,” she said. “I think GW students in particular will end up in leadership positions, and I want them to have some understanding of these issues.”

She hopes the safer chemicals movement will catch on in her field over time. “This is exploratory. It’s very new. But we need to think about the molecules we’re bringing into the world.”