By John DiConsiglio

Like anyone who has boarded a plane, the students in Associate Professor of Psychology Stephen Mitroff’s freshman seminar Science in the District were all too familiar with the headaches and hassles of airport security. They knew about long lines at checkpoints as passengers removed their shoes and security officers searched through carry-on bags. And more than a few students admitted they had rolled their eyes and wondered if the security employees couldn’t do their jobs a little bit better.

But that was before Mitroff’s class gave them a peek behind the curtain—and they saw airport chaos from a cognitive psychology point of view. During a field trip to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) headquarters at Reagan National Airport, the students trained a watchful eye on the multitude of factors that come into play when thousands of passengers rush through security gates—from the angle and detail of computer monitors to whether an officer got enough sleep the night before. They looked for clues to impaired visual perception. Were the tables too cramped? The alcoves too noisy? Were there too many display screens? Too few?

“Most of [my students] have gone through security and all they probably thought about was how fast they got to their gate,” said Mitroff. “But when you actually see what’s going on, you get a deeper understanding of everything everything involved. Security personnel are tasked with opposing jobs: get everyone through quickly but don’t let anything dangerous slip by. They rely on perception, decision making and memory.” In short, he said, they rely on cognitive psychology.

| Associate Professor of Psychology Stephen Mitroff (Photo: William Atkins) |

Cognitive-psychology-in-the-real-world was at the forefront of Mitroff’s mind when he created the freshman seminar, which he taught for the first time last fall and which will return in fall 2016. Like other Dean’s Seminars, Mitroff’s offered a small class (just 19 students) on a concentrated topic. But he also designed his curriculum to take advantage of the proximity to D.C. institutions, planning field trips to agencies like the TSA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration as well as health care facilities like the GW Breast Imaging and Intervention Center and the MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH). The goal, he told his students, was to augment their classroom lessons with examples of cognitive psychology principles in action.

“You so often think of psychology as an academic subject or a clinical one,” said Emily Polansky, a freshman who plans to major in psychology, “but [in Mitroff's class] we looked behind the scenes at how these concepts are used every day, in places you never imagined.”

One Foot in Theory, One in Practice

A broad branch of scientific study, cognitive psychology involves brain functions like learning, attention and perception. While these can seem like abstract concepts, Mitroff explained that they are the cornerstones of many professions. From the pilot who must recognize which of several hundred switches to pull at the right moment to the ER nurse who monitors a floor full of patients for the first sign of trouble, many jobs hinge on applying cognitive psychology to practical problems. That’s Mitroff’s personal specialty. Working with organizations as disparate as the U.S. Army and Department of Homeland Security to Nike, Mitroff has studied how professionals use cognitive psychology concepts with the hope of improving their job performance. He’s worked with tools like a smartphone app that might help TSA officers find contraband and strobe-light eyewear that Nike designed to potentially strengthen sports vision.

“As a cognitive psychologist, I keep one foot in theory and one in practice,” he said. “I take ideas about the way we see and remember things and then connect them to the processes by which people actually do their jobs. By understanding their professional experiences, we can help advance scientific theories and, in turn, hopefully, we can help them do their jobs better.”

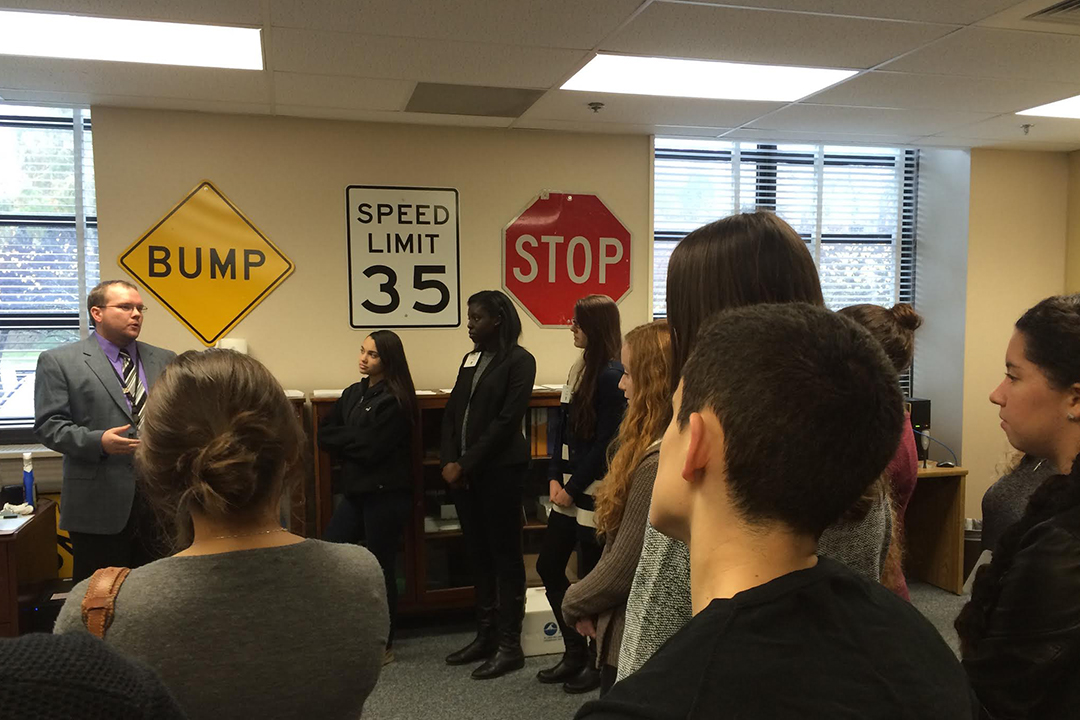

Students in Mitroff’s freshman Dean's Seminar on Science in the District. Students in Mitroff’s freshman Dean's Seminar on Science in the District. |

During the field trips, students witnessed professionals employing cognitive psychology tools. Driving simulators at the Traffic Safety Administration bombarded users with distractions from oncoming traffic to incoming texts. Before visiting the GW Breast Imaging Center, the class read articles on how interruptions like ringing cell phones can impair radiologists’ performance. Most of the students were incredulous, Polansky recalled. But after touring the cramped, dark imaging rooms and speaking to doctors logging long shifts, Polansky could appreciate their plight. “The people who do these jobs don’t just clock-in and stop thinking about their kids or how tired and hungry they are. These are real people in real situations,” she said. “When their phone rings, they are going to glance at it.”

At the rehab hospital, students saw one of Mitroff’s own studies at work. Along with Associate Professor of Psychology Sarah Shomstein and graduate student Breana Carter, Mitroff is teaming with NRH occupational therapists to test whether the Nike strobe eyewear might aid stroke patients recovering from visual impairments. To Isabel Pellegrino, a freshman journalism major, the most memorable part of the seminar was seeing Mitroff interact with a stroke victim who was using the eyewear as part of the study. The patient turned his wheelchair to the students and flashed a thumbs-up.

“That was very powerful,” Pellegrino said. “It was awesome to see my professor talking to this man and trying to do something for him. It made what we were learned in class feel so real.”