It was the first building constructed on George Washington University’s Foggy Bottom campus—and maybe its most historic. It’s been the site of some of the greatest breakthroughs in fields like physics and chemistry, the spot where George Gamow devised the Big Bang theory and Niels Bohr announced the dawn of the Atomic Age. The bazooka was even developed in its basement.

It’s Corcoran Hall, the brick and limestone home to generations of scholars and students. And in October, the science landmark on 21st Street will turn 100 years old.

Today, the building—which is listed on the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites and the National Register of Historic Places—primarily houses the Physics Department at the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences (CCAS). For nearly 90 years, the CCAS Department of Chemistry was also based there before the opening of Science Engineering Hall in 2015.

To kick off its centennial anniversary, Corcoran Hall will host a slate of events at GW’s Alumni & Family Weekend, including the CCAS Dean’s Breakfast Reception, lectures on the building’s storied history, and tours for alumni, families and friends. The celebration will also highlight the breakthroughs today’s physics faculty and students are making in its state-of-the-art classrooms and laboratories.

“This building has a very rich history. Some literally world-changing things have happened here—and great things are still happening here,” said Physics Chair and Associate Professor Alexander J. van der Horst. “We continue to have great opportunities for students. And we continue to do the kind of research that put this place on the map.”

Indeed, throughout the historic building—in the same spaces where pioneers like Gamow, Edward Teller and chemist Charles Naeser investigated sciences wonders from the nucleus of the atom to the genetic code of life—GW scholars have carried on a legacy of innovation, van der Horst explained.

At Corcoran Hall, for example, Professor of Chemistry Akos Vertes, a fellow of the National Academy of Inventors, began his early work on protein molecules; Professor of Physics Chryssa Kouveliotou, a National Academy of Sciences member, is pioneering advancements in high-energy astrophysics; and Professor of Physics Neil Johnson, a fellow of the American Physical Society, is unlocking complex systems that influence activities from social media behavior to artificial intelligence use.

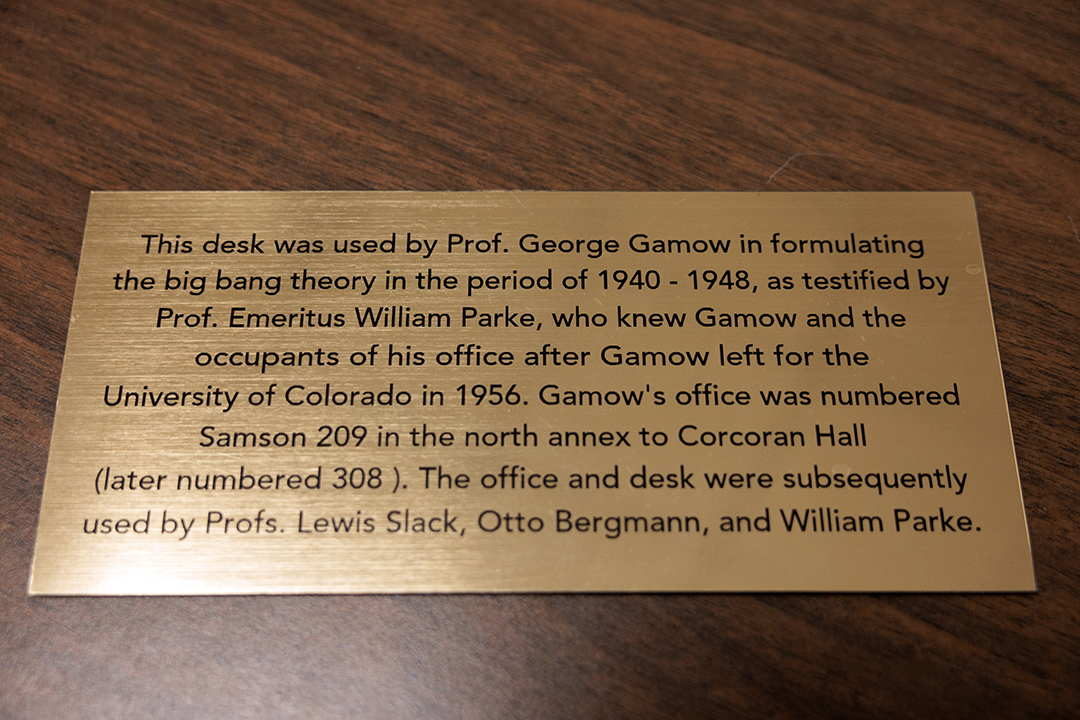

Gamow’s original desk—where, according to legend, he had his Big Bang “eureka!” moment—is still on display in a Corcoran Hall office for Physics Department visitors. And Assistant Professor of Physics Axel Schmidt actually works at Teller’s desk—delighting his friends who saw the “Father of the Hydrogen Bomb” portrayed in the movie Oppenheimer. “It’s a weighty thing to sit at his desk,” Schmidt said. “But it’s also the first thing I tell people.”

Then and Now: Corcoran Hall past and the landmark building on 21st Street today.

In the same spots where Oppenheimer-era physicists explored the building blocks of the universe, today’s students conduct their own experiments in the hands-on SCALE-UP classrooms. And in the same basement birthplace of the bazooka, the award-winning GW chapter of the Society of Physics Students (SPS) organize their activities and outreach. “The [building’s] history is definitely something I think about,” said SPS President Quinn Stefan, a senior physics major. “It’s a cool feeling to know that you are a part of such a rich legacy—and you’re adding to it.”

Center of Science

Not long after the October 28, 1924, dedication of Corcoran Hall, the building became the center of the science universe. Gamow, already renowned for his foundational work on quantum theory and nuclear particles, was recruited to GW in 1934. He had two conditions before joining the physics faculty: He asked to bring friend and colleague Teller along and he wanted to organize yearly physics conferences.

Those annual meetings—or “witches Sabbath” as Gamow dubbed them—brought some of the most prominent scientific figures of the time to Foggy Bottom, including Enrico Fermi and Robert Oppenheimer himself. At the 1939 conference, Nobel Prize winner Bohr announced the splitting of the uranium atom—ushering in the Atomic Age.

Gamow would go on to advance significant physics principles from his desk at Corcoran Hall—including early work on unraveling the DNA structure codes for proteins.

Three plaques commemorating (from left) Gamow, Teller and the Atomic Age are on display outside the building.

Belgian priest and physicist Georges Lemaitre first heard about astronomer Edwin P. Hubble’s research at a Corcoran Hall meeting of the American Astronomical Society in 1925—leading to their groundbreaking law on the expansion of the universe. And during World War II, government contracts supported the development of new technologies like the bazooka—based on work by Chemistry Department head Charles Edward Munroe, the inventor of smokeless gunpowder.

“There have been some amazing things that have gone on during the 90 years the Department of Chemistry…resided in Corcoran Hall,” said Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Michael M. King, “from the contract work prior to and during World War II, the many veterans who returned to campus after the war, the bumpy years of Vietnam War protests and generations of amazing students and incredible discoveries.”

“A Special Place”

Even van der Horst wasn’t fully aware of the building’s history when he joined the department in 2015—but he found out soon enough. “From day one, everybody talked about it,” he said. “It is part of the fabric of the department.” SPS’s Stefan learned about the milestones in van der Horst’s astrophysics classes, “I remember thinking ‘Wow, [Gamow] worked on these incredible theories that advanced the field in this very building. Meanwhile I’m struggling through an undergraduate class in here,’” she laughed.

Not all aspects of the century-old building were remembered with nostalgia. Before its 2016 renovation, Vertes recounted crawling through Corcoran Hall ceiling panels to string coaxial cables; King recalled “the incredibly quirky ventilation systems…and an elevator that shakes”; and van der Horst described the bazooka basement as “creepy.”

But since reopening in 2018, the building added a cutting-edge Innovation Lab and the interactive SCALE-UP classrooms where students perform real-time experiments. In addition to SPS, Corcoran Hall also headquarters GW’s Women & Gender Minorities in Physics Group (WGMiP), which promotes “the inclusion, participation, and success of underrepresented genders in physics,” noted WGMiP president Olivia Nippe-Jeakins, a junior astronomy and astrophysics major.

“The community is why this building is such a special place,” Stefan said.

New faces of science: Left, an early physics lab at Corcoran Hall. Right, undergraduate physics majors (from left) Quinn Stefan and Olivia Nippe-Jeakins in the building’s modern Innovation Lab.

Meanwhile, the Physics Department continues building on Gamow’s legacy, van der Horst said, particularly in the famed physicist’s main focus areas: nuclear physics, biophysics and astrophysics. Van der Horst isn’t making any predictions about the next 100 years at Corcoran Hall—but he noted that faculty and students are always exploring emerging fields like quantum computing, AI and machine learning.

“I can’t foresee the many accomplishments that will happen here 10 years from now—let alone 100,” he said. “But whatever the next big thing is, the faculty and students in this building will be ready for it.”