By John DiConsiglio

Priya Dhanani, MA ’14, draws confused looks each time she steps into a Washington, D.C., high school. She’s prepared a four-hour presentation on human trafficking. The students are expecting a dull lecture from a cop or a nurse. Instead, Dhanani hits play on her iPod and the booming rhythms of rapper 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.” fill the classroom.

Now shorty, she in the club, she dancin' for dollars

She got a thing for that Gucci, that Fendi, that Prada…

She's feeding fools fantasies, they pay her cause they want her

An hour later have [her] up in the Ramada

Invariably, the teens sing along to the familiar tune. That’s when Dhanani asks them to think about the words. This isn’t a party song. It’s not about dancing at a club. It’s about sexually exploiting a young girl. And worst of all, the lyrics imply that it’s exactly what she wants.

“That’s the light bulb moment,” Dhanani said. “They start to realize what human trafficking really looks like—a young person exploited in exchange for money, clothes, affection. And not only do we often glorify that culture, we even go as far as blaming the victim.”

Dhanani knows how to turn preconceived notions on their head. As the director of prevention education for FAIR Girls, a D.C.-based nonprofit that works to eradicate child sex trafficking, she conducts as many as four presentations a week, reaching 3,000 young people in schools, shelters, detention facilities and youth centers—as well as hundreds of adults from social service agencies, law enforcement and teaching. And despite the varying ages and expertise of her audience, she encounters the same stereotypes.

“People think of this life as a choice. They still use those derogatory terms like slut and ho,” she said. “Our message to them is simple. These aren’t party girls. They are exploited children. And it’s not their fault. It’s never their fault.”

Fighting an Epidemic

Youth sex trafficking is a hidden epidemic, a $32 billion industry that ensnares 1.2 million children each year. An estimated 100,000 children are sexually exploited in the U.S. alone, most beginning from the ages of 12 to 14.

Youth sex trafficking is a hidden epidemic, a $32 billion industry that ensnares 1.2 million children each year. An estimated 100,000 children are sexually exploited in the U.S. alone, most beginning from the ages of 12 to 14.

But, when most people hear “trafficking,” they think of a young person’s shadowy abduction into a seamy underground network, Dhanani explained. The true face of trafficking strikes closer to home; 65 percent of the victims are runaways, most of whom have fled because they have been molested or exploited by someone close to them. Far from the Prada-chasing party girls in 50 Cent’s song, they are usually vulnerable, neglected and lack basic necessities like food and shelter. In exchange for what first seems like a helping hand—money, affection, even a meal and a place to sleep—they are routinely raped an average of five times a night.

Dhanani once knew as little about trafficking as her students, until she discovered that a house in her well-manicured Atlanta suburb was actually a brothel. “I always thought those places were run-down shacks in big cities,” she said. “But there it was, right next to the Subway shop and the strip mall.”

Her eyes opened to the realities of the sex trade, Dhanani volunteered for anti-trafficking causes throughout high school and college. Even before she began her sociology graduate studies at Columbian College in 2012, she moved to Washington to work for FAIR Girls, which offers outreach and education programs as well as direct services to young victims of sex trafficking. The organization works with survivors to find jobs, housing, lawyers and medical resources.

Dhanani’s “boots on the ground” experience, as Associate Professor of Sociology Ivy Ken put it, gave her a unique vantage point while pursuing her degree. “Most people think of sociology as all theory, when in fact it gives you a broad lens to understand almost any issue—from violence and trafficking to housing and food issues—and prepares you to put your degree to work,” Ken said. “Priya is doing just that. She’s applying her studies by helping real people on a day-to-day basis.”

The FAIR Girls’ anti-trafficking curriculum, entitled “Tell Your Friends,” is taught in six states, from schools in Houston to shelters in Wichita to police stations in Baltimore. Using video, drawing and song, the interactive curriculum defines human trafficking, identifies risk factors for teen girls and boys and talks about healthy and unhealthy relationships.

FAIR Girls also operates programs outside of the U.S. Dhanani is currently working with partners in Russia to create an online Cosmo-style quiz that helps young woman in both countries connect with resources if they are at-risk for trafficking.

A Hot Topic

Prevention and education efforts are making an impact, Dhanani believes. Recently, President Obama announced new anti-trafficking initiatives, including the first-ever national assessment of the problem and a $6 million grant to organizations like FAIR Girls that aid trafficking victims. In D.C., among the 10 worst American cities for human trafficking, the city council passed a bill that ensures child victims receive support services, instead of being arrested for prostitution. And while movies like Liam Neeson’s Taken are typically inaccurate, they have thrust the issue on to the public’s radar. “It’s a hot topic,” Dhanani said. “People are talking about it more than ever. And any dialogue is good dialogue.”

With 50 Cent's "P.I.M.P." thumping in the background, Dhanani talks to D.C. high school students about abusive relationships, and presents resources they can use if they are being exploited. But she still hears push-back when she asks students to describe traffickers and victims—comments like “Sure, the pimp is bad, so why didn’t she leave him?” Or “When she’s wearing a skirt that short, you know she’s looking for it.”

When the class breaks for lunch, Dhanani collects the students’ confidential comments cards. They tell a different story: "What can I do to help a friend who is being hurt and exploited?" "I have an older boyfriend who is pressuring me to have sex and do things. Should I just give in?” “I always thought I deserved it. I didn’t know it wasn’t my fault.”

“Some days, this job makes me feel like a very tiny person battling an enormous issue,” Dhanani said. “Other days, I walk away from the classroom feeling like I may have gotten through to someone, that maybe I planted a seed.”

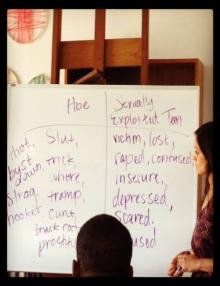

Image: Dhanani asks students to draw pictures of what they think trafficking looks like, as in this drawing by a Washington, D.C. teen.