By John DiConsiglio

On a typical day at the George Washington Speech and Hearing Center, Jordan Sender, a second-year graduate student, might spend her afternoon leading a stroke patient in vocal exercises as he struggles to regain communication skills. Or she might guide a client with Parkinson’s Disease through a software program that allows him to monitor his voice’s volume and tone. Or she may end up corralling a feisty four-year-old with apraxia—a disorder that prevents the brain from organizing intelligible sounds—and persuading him that it’s more fun to play with her colorful flashcards than race around the brightly painted treatment room.

But patient treatment isn’t the only job for Sender and each of the 64 students in the Speech-Language Pathology Graduate Program, which requires the completion of a series of rotations at the clinic. Sender is just as likely to fill her hours puzzling over insurance forms, solving scheduling snafus and making sure the clinic rooms and equipment are infection-free.

“I thought I was prepared for anything,” Sender said. “The clients, the research, the classes—I knew what I was getting into. But there’s a lot more going on here.”

“Intensive. Demanding. Rewarding.” That’s the way second-year graduate student Katie Winters describes the Speech and Hearing Center experience. For two years, including a summer semester, students supplement their classroom work and lab assignments with all the practical duties and responsibilities involved in clinic management. They not only hone their diagnostic and treatment skills; they become polished pros in everything from payments to paperwork.

“We essentially give them the clinic,” said Michael Bamdad, the center’s director. “It’s up to them to make sure everything in it runs properly.”

Most speech pathology programs offer students some degree of client-interaction, Bamdad noted. But GW’s clinic is unique in the diversity of clients and the range of responsibilities—from patient treatment to clinical research to administrative tasks. “Students work harder than they ever have in their lives,” Bamdad said. “But when they graduate, they are prepared for anything the field throws at them.”

Each student is required to perform a four-month rotation and see clients impacted by conditions relating to audiology, aural rehabilitation, voice disorders, adult neurologic disorders resulting from brain injuries or strokes, literacy challenges, fluency issues such as stuttering , motor speech disorders, and developmental issues like autism. While certified speech pathologists and instructors keep a watchful eye on patient sessions, students devise their own treatment plans and assessment tools, relying on everything from evidence-based research to experimental technology and techniques.

“It’s important to put the students in the lead,” Bamdad stressed, “The patient should see them as the caretaker.”

In-Demand

Speech pathology is a burgeoning field with employment opportunities expected to rise by 19 percent in the next 10 years—higher than the average for any other occupation, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. With the high-demand for jobs in schools, hospitals, rehab centers, nursing homes and even private practice, students are stepping into a promising career market. “We produce very qualified, job-ready graduates,” Bamdad said. “Parents love us!”

Indeed, Winters, who also received her BA in speech and hearing sciences from GW in 2013, chose the program for its post-graduate job potential. It balanced her dual interests in science and communication while also providing a clear career path. “When I was looking at colleges, I was determined to find a program that would result in a stable job,” she said. “I knew from day one that this is what I wanted to do.”

The treatment rotations are complemented by the clinic’s on-site research lab. For example, in addition to collecting data for her own thesis on societal perceptions of stutterers, Winters is assisting Assistant Professor Cynthia Core and Associate Professor Shelley Brundage with research on bilingual language development. And Sender will co-author a journal paper with Bamdad on brain injury cases of people who have lost the ability to lie or recognize sarcasm. Together, their research focuses on therapy to ease these often socially-awkward patients into societal structures, where they may struggle to maintain jobs and relationships.

Face-to-Face With Clients

Once the clinic doors open, students often find that sitting across from a real-life client can feel like a different world than their classrooms or labs. “Here’s someone who is paying for your services and hoping you will help them, and you feel like you aren’t exactly sure what you are doing,” Sender said. “You can practice in class. You can observe as an undergraduate. But when it’s just you and that person face-face, it’s intimidating.”

Winters quickly learned that client interaction requires as much patience as technical prowess. While walking a stroke patient through a sentence structure activity, she noticed her client growing increasingly frustrated by his lack of success. Rather than push him forward, she put the exercise aside and lent him a sympathetic ear. By the time she looked at her watch, the session had ended. Winters expected her supervisor to chastise her for wasting an hour. Instead, he complemented her empathy. “He said that sometimes clients need to talk more than they need the session you had planned,” she said.

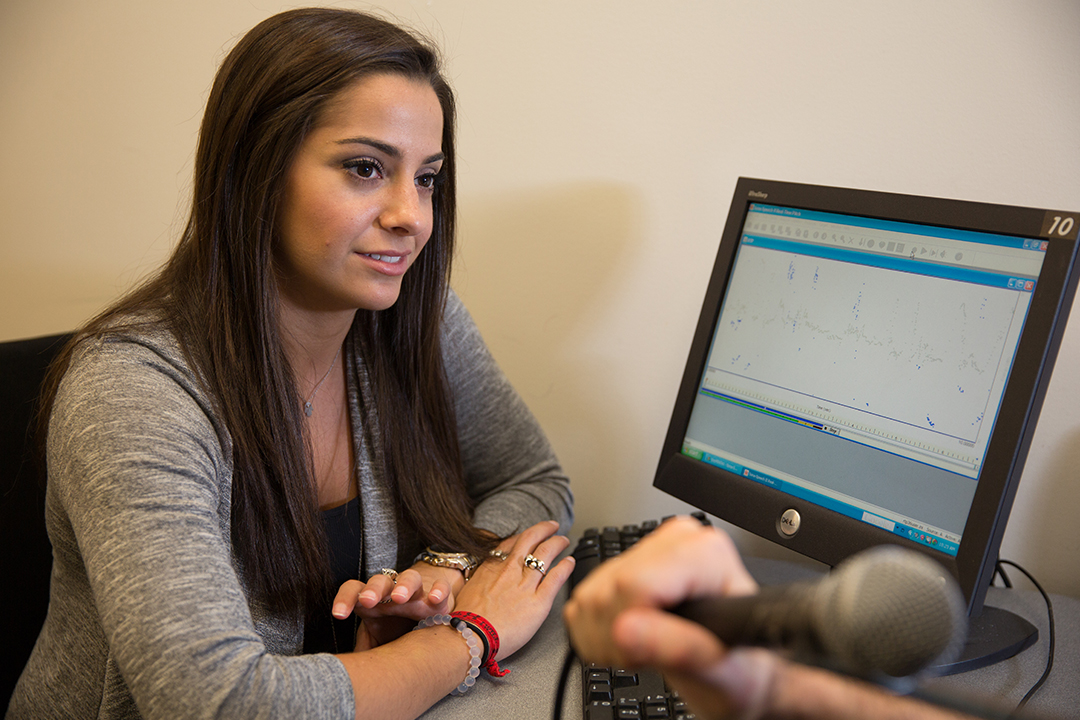

And the hard work often pays off with more than a career-ready degree. The center regularly works with male-to-female transgender clients through the laborious process of acquiring a feminine sounding voice. Using software called Visipitch, students and clients can measure changes in tonal frequency and pitch. Sender recalled working with a transgender patient who had only recently begun to self-identify as a woman. She took her first hesitant steps in Sender's treatment room to alter the cadence of her deep masculine voice. After their four-month session, Sender worried that she had made little progress—and that the student had been unable to guide her patient through a tumultuous time. But weeks later she received a thank-you note from the client, saying their sessions had inspired her to persevere with her transition.

“We are working with people who are struggling with the basic ability to communicate,” she said. “The best days are when you go home knowing you made their lives a little bit easier.”